I have written a previous post about my quest to discover the medieval origins of the position of King’s Champion. Rather than rehashing it, you can find it here.

So following the work I did for the previous post, I decided I needed more information than my collection of books and what I’d so far managed to find online could provide. So I headed for the State Library of Victoria. It’s one of my favourite places to do research and if you’re not familiar with it you can see the famous domed reading room in the photos below. I always work in here whenever I can because it has an extensive collection and the most amazing atmosphere.

In the reading I’d been doing for my previous post many of the 1800s sources on the King’s Champion I’d found had been based on the work of William Dugdale. I decided he would be a good person to begin the next stage of my search with. Primarily to see if he had any references in his work that would let me track back further. I discovered he was a writer in the 1600s who wrote extensively about both baronial families and peerage. I also found that the State Library had a copy of his two volume work The Baronage of England or The Historical Account of the Lives and Most Memorable Actions Of Our English Nobility. The first volume covers from the Saxons, to the Norman Conquest, to those who had their rise before the reign of Henry III. The second volume covers from the end of Henry III’s reign to the reign of Richard II. It was the first volume I was most interested in as it was this that later writers were referencing when discussing the Marmion family’s heritage.

I ordered both the books from the State Library. They are classified as rare books so I had to view them in the heritage reading room. Rare books is a wide ranging definition. A book can be rare due to age, or fragility, or a lack of copies in existence as well as other reasons. I was expecting an 1800s copy of the work as this is what usually happens. So I was delighted to find that what I’d ordered was actually a printing from 1675. This is one of the things I love about libraries like the State Library of Victoria. They have an amazing range of rare, fragile and obscure items but you don’t have to have any special qualification to access them. They are there for the use of all Victorians. All I needed to access these books was my library card. I was very excited as this is now my record for the earliest book I have ever held. It beat one from the mid 1700s I used for researching William Marshal during my honours year. The title page of Dugdale’s book can be seen below.

The first volume indeed had the peerage of the Marmion family. It begins by saying that William I gave Robert Marmion the castle of Tamworth. The Domesday Book lists Tamworth castle as being in the hands of the king in 1086. William I died in 1087 so it is just about possible that he gave the castle to Robert Marmion. What is most interesting is the entry regarding the Marmion family and Scrivelsby, the manor which is now tied to the role of King’s Champion. It is only mentioned once and this is not until the narrative reaches Phillip Marmion who died in the 20th year of the reign of Edward I. In this case it is just a passing mention. Scrivelsby is listed as of one of the properties Phillip held by right of Barony on his death. You can see the passage on the page below.

Dugdale does provide references as to where he is getting his sources. Unfortunately he does it in an abbreviated form, but doesn’t explain what the abbreviations mean. I am yet to work out exactly what the reference for Scrivelsby is referring to, but when I work it out I’ll track it down. The other telling thing about this book is the lack of any kind of reference to the Marmions as hereditary Kings Champions. This doesn’t prove that they weren’t of course, but it might mean that it wasn’t well known or considered especially important.

I also examined the second volume of Dugdale’s work, but there were no further mentions of the Marmions or of the Dymoke family, the family who inherited the title of King’s Champion. What Dugdale does give the reader is what seems to a be a reasonably accurate account of the individual Marmions in England in the Norman and early Plantagenet times. So it seems likely that whether or not they were official King’s Champions, or hereditary Champions of Normandy, that the Marmions were in England roughly from the time of William I. There is also a second Dugdale work that apparently does discuss the role of King’s Champion that I am hoping to track down soon.

Having determined that most likely the Marmions were in England in some form from the time of William I, I decided to try a slightly different track. I’d been looking into the household of the king because the King’s Champion is often mentioned in coronations alongside positions such as the Marshal. From work I’d done on William Marshal I knew that the Marshal is definitely an hereditary position and that it was certainly considered a part of the king’s household. So I decided it was worth having a look through one of the best records of a king’s household from the early Plantagenet period. The Constitutio Domus Regis is a contemporary account probably of the household of Henry I. The exact date is still under debate. It has thankfully been translated by S.D Church. The State Library has a copy which also contains the translation, by Emile Amt, of the Dialogus De Scaccario (the Dialogue of the Exchequer) which dates to the 12th century. I have gone carefully through the Constitutio and am unable to find any mention of the King’s Champion. I also can’t find any kind of regular payment to the King’s Champion listed in the Dialogus. Again this doesn’t mean that it didn’t exist in this time, it may just not have been included in these particular documents. It could also mean that if it did exist then it was much less formal an appointment than say the Marshal, and may have not had a day to day role.

Continuing on a slightly different track I decided that exploring the question from the point of view of the coronation itself was a good idea. Other sources I’d been reading referenced two books

1. The Coronation Book of the Hallowing of the Sovereigns of England. By Jocelyn T. Perkins published 1902

2. English Coronation Records Edited by Leopold G. Wickham Legg published 1901.

The State Library had copies of both. I began with The Coronation Book. While this text doesn’t provide any revelatory new information it does cover the position of King’s Champion in later years in detail and provide some lovely little vignettes of the Champion’s role in the coronation. For example John Dymoke entrance as the champion to Richard II. When he appeared at the coronation on his ‘mighty steed’ he was summarily told that he had come in at the wrong time and told to come back later when it was appropriate.

The Coronation Book provides extensive discussion of many of the ceremonies that various Champions after the reign on Richard II were involved in. It doesn’t however provide any information as to the the role of the Champion before the reign of Richard II. What it does do though is give some lovely illustrations and photos. Some are non contemporary illustrations of the Champions performing their duties and others are of the Champion’s acroutements. They can all be seen below.

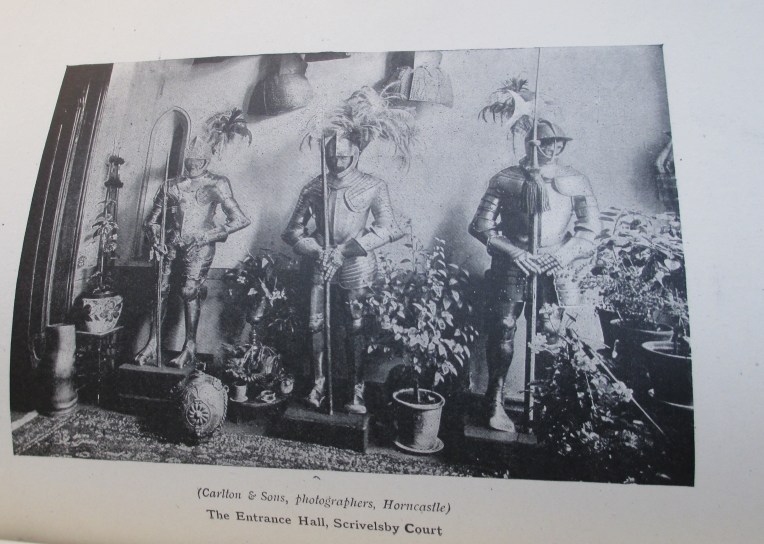

The Manor of Scrivelsby which is currently tied to the position of Champion.

Some of the suits of armour worn by the Champions.

The cups which are the official payment to the Champion for their service at the coronation.

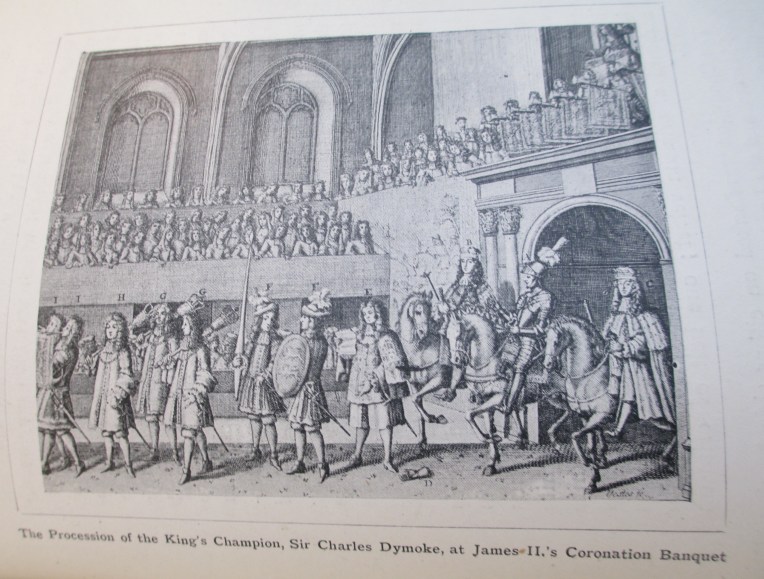

Sir Charles Dymoke James II’s Champion

Henry Dymoke the Deputy Champion.

Henry Dymoke participated in George IV’s coronation because the Champion John Dymoke (Henry’s father) was a cleric and therefore apparently unable to undertake the role. The only other time a Deputy Champion was used was at the coronation of Richard II when the hereditary Champion was Margery Dymoke. Her husband John Dymoke undertook the role by right of his wife as she was a woman and as such unable to be to be Champion. [1]

Margery and John Dymoke actually raise a very interesting point which is briefly discussed in The Coronation Book. The coronation of Richard II is the first record we have of the Champion’s role in the coronation. It is also the period in which the Dymoke family took over from the Marmions as the Champions. The Coronation Book mentions that there was a case in the Court of Claims before Richard II’s coronation. John Dymoke argued his right to be Champion through his wife’s descent from Phillip Marmion and his possession of Scrivelsby. [2] When I found this I realised that this court case would be absolutely key because it would have to include an explanation of the rights of the Marmions to the position of King’s Champion. The Coronation Book doesn’t really provide that much more detail, but thankfully the second book I listed above, English Coronation Records, does.

English Coronation Records in fact has a transcription and translation of the court case. It’s reasonably long and as such I won’t present it in full here. In summary John Dymoke and Baldwin de Freville both presented their cases to be the King’s Champion. Both of them were claiming the position of Kings Champion due to their descent, through marriage, from Phillip Marmion. Phillip was the last of the main line of Marmions and he died in the reign of Edward I. John held Scrivelsby and Baldwin held Tamworth. There were fierce arguments on both sides. In the end it was decided that as John had presented a better case and crucially because “several nobles and magnates appeared in the said Court and gave evidence before the said Lord Steward, that the said Lord King Edward and the said Lord Prince lately dead frequently asserted, while they lived, and said that aforesaid John ought of right to perform the aforesaid service for the said Manor of Scrivelsby.” [3] This last point is absolutely key because this is the point where the role of Champion is tied irrefutably to Scrivelsby itself rather than the specific family.

So through all this I have still failed to find definitive evidence that the Marmions were the hereditary Champions. It does seem, however, that they were certainly believed to be the hereditary Champions in 1367 at the time of Richard II’s coronation. Baldwin and John were both arguing on hereditary descent from the Marmions not specifically on the possession of their respective manors. Additionally no one in the court seemed to find this claim odd and several nobles seemed to feel that Edward III and Edward the Black Prince had discussed it, so it must have been a position that was known and understood.

I am still not quite finished with this. I’m hoping to track down the other Dugdale book in which he apparently discusses the role of the King’s Champion, as well as deciphering his abbreviation style. I am also going to look into the Marmions specifically, as it seems clear that the role was tied to their family not to the property of Scrivelsby until 1367. I am going to see what I can find out about their role in Normandy where they were supposedly hereditary Champions. If I find anything I’ll post an update.

[1] The Coronation Book of the Hallowing of the Sovereigns of England. By Jocelyn T. Perkins published 1902 p.151

[2] The Coronation Book of the Hallowing of the Sovereigns of England. By Jocelyn T. Perkins published 1902 p.134

[3] English Coronation Records Edited by Leopold G. Wickham Legg published 1901. pp. 160-161

The photos are all mine.

Criccieth Castle

Criccieth Castle

Dolbadarn Castle

Dolbadarn Castle

Dolwyddelan Castle

Dolwyddelan Castle

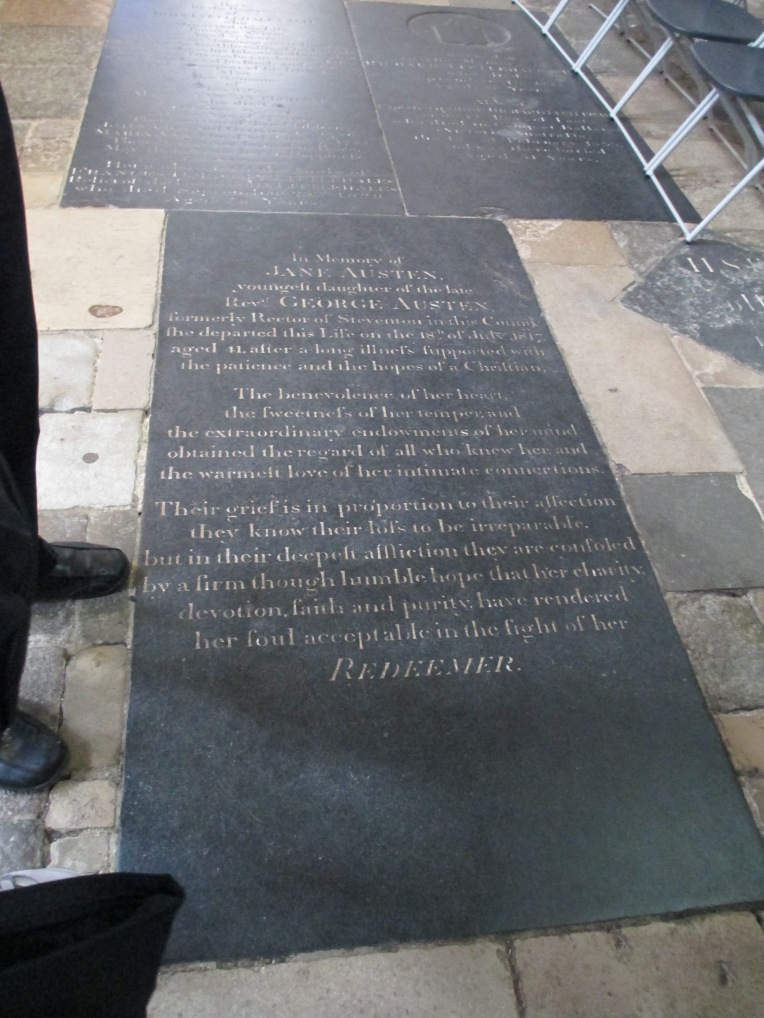

Winchester Cathedral has a long history. A Saxon cathedral was begun on this site in c. 648, but was slowly replaced by the Norman Cathedral and finally demolished in 1093 when the old and new building converged. You can see the outline of the original Saxon cathedral laid out below.

Winchester Cathedral has a long history. A Saxon cathedral was begun on this site in c. 648, but was slowly replaced by the Norman Cathedral and finally demolished in 1093 when the old and new building converged. You can see the outline of the original Saxon cathedral laid out below.

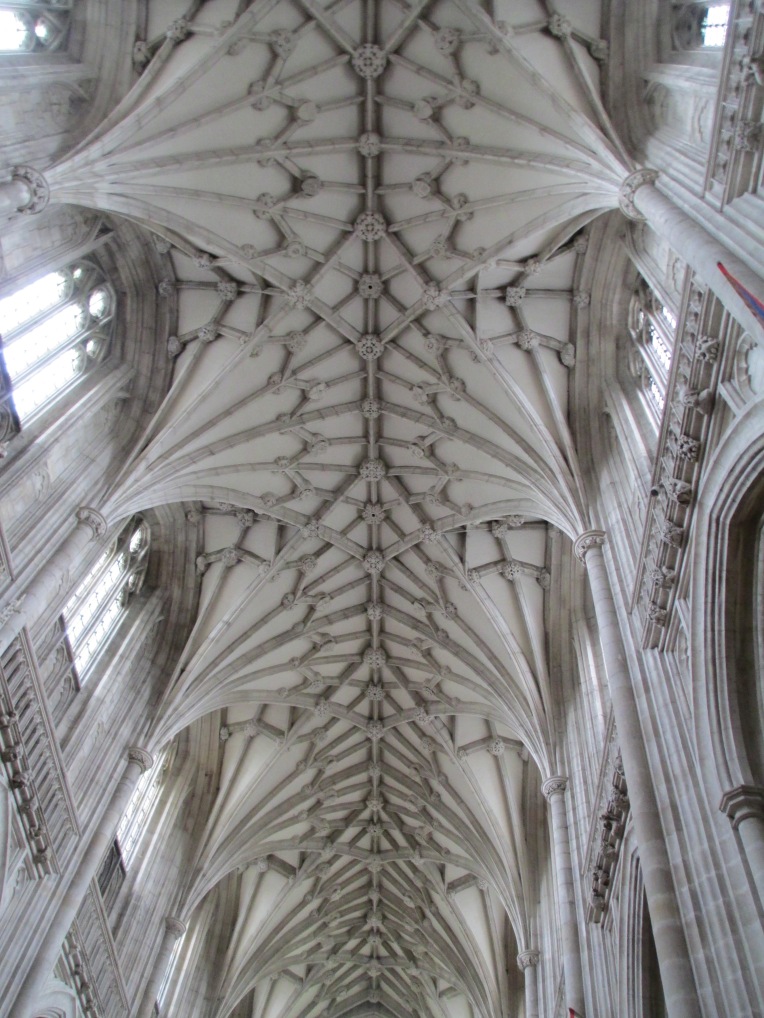

The romanesque style of the earlier cathedral can still be seen, specifically in the north transept (see below). The roof, in the Tudor style, in the photos below was inserted in 1819. The figure of Christ you can see in the first photo is by contemporary sculptor Peter Eugene Ball and was gifted to the cathedral in 1990.

The romanesque style of the earlier cathedral can still be seen, specifically in the north transept (see below). The roof, in the Tudor style, in the photos below was inserted in 1819. The figure of Christ you can see in the first photo is by contemporary sculptor Peter Eugene Ball and was gifted to the cathedral in 1990.

Another beautiful surviving element found in Winchester is the font. It dates to c.1150-1160 and is thought to be a result of the patronage of Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester. It’s made of Tournai marble, which is in fact a dark limestone, and is carved with scenes from the life of St Nicholas.

Another beautiful surviving element found in Winchester is the font. It dates to c.1150-1160 and is thought to be a result of the patronage of Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester. It’s made of Tournai marble, which is in fact a dark limestone, and is carved with scenes from the life of St Nicholas.

The scene you can see in the image above is thought to depict the story that St Nicholas slipped money into a house to stop a nobleman from being forced to put his daughters onto the street.

The scene you can see in the image above is thought to depict the story that St Nicholas slipped money into a house to stop a nobleman from being forced to put his daughters onto the street.

Answer:

Answer:

Answer:

Answer:  Answer:

Answer: