I’d like to begin this post by acknowledging that Murtoa, the town I’ll be talking about, is on the lands of the Jadawadjali people. It always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

Welcome to another addition of Ragbag on Road. As you can see from the above video- in this iteration you find me in the incredible Murtoa Stick Shed.

To give you some context, Murtoa is a town in the Wimmera region of Victoria. You can see it on the map below.

And as you can see from the photos below it isn’t a large town.

The Stick Shed from the outside is certainly not remarkable.

But inside it is glorious

What makes the Stick Shed so remarkable visually is its sheer size (which doesn’t quite translate in photos). It’s 270m long, 60 m wide and 19 m high, and it is made up of 560 unmilled poles, hence the name ‘Stick Shed’, officially it is called the The Murtoa No.1 Store. You can see a photo of me in the Shed below to give you some concept of scale.

But the Stick Shed is more than a folly of sticks. It had a purpose and stands at the heart of the agricultural history of the region, which is why it was added to the Victorian Heritage Register as number 101 in 1990.

So what is that history?

For that we’ll need to go back to the beginning.

The genesis of the Stick Shed lies in World War Two.

Prior to the war, Australia’s main grain export market was Europe, and Great Britain specifically. With the advent of war, and subsequent threat to shipping, this market dried up and when Japan joined the war in 1941 any attempts to expand into the Asian market was kiboshed completely. The situation wasn’t helped by the fact that there was a wheat glut as well, especially in Western Australian, so the wheat could not even be used domestically.

So the Australian Wheat Board was faced with the question of what to do with all the extra wheat? The silos were already full, they needed another option. So they started building massive grain sheds in WA (the glut reached capacity there first). They were successful, so the local Grain Elevator Boards in Victoria decided that they needed one too. Murtoa was selected as the best site. This form of mass storage wasn’t a universally popular decision, with opposition from some labour forces and the (surprisingly) influential jute bag industry.

But why Murtoa?

It’s actually a fairly simple answer: Murtoa was in the middle of a wheat producing region, it had major rail and road connections, the local town conveniences needed and was at the confluence of another rail line that fed grain to the North.

Alright, so we know what the point of the Stick Shed was, and why in Murtoa, but how did something so practical come to be so remarkable? The first reason is the sheer size needed, as discussed above, and the second is the decision to use unmilled timbers. The choice of timber was determined by a shortage of steel. The timber is mountain ash hardwood, and it all comes from Victoria. Mainly the Otways, Gippsland and the Dandenong Ranges. There is an astonishing 2000 tonnes of timber in the structure. What is even more astonishing is the speed with which the Shed was constructed. It was built in only 4 months, starting at the end of 1941 and opening on the 22nd of January 1942 when the first bags of wheat were deposited by local farmer Maurice Delahunty. The first railway load of wheat arrived in February and by May/June the Stick Shed was filled with 3,381,600 bushels of wheat. The wheat remained undisturbed until 1944.

The Shed was built largely by hand (it’s a testimony to its importance that the government managed to provide a large workforce in war time). The poles were carted in from all over the state and erected in the hard Wimmera clay largely using trucks and A-frames- no big machinery. You can see some photos below that give you an idea of the process.

One of the key features that differentiated the Shed from others was the concrete floor, others had tin that failed to keep out the vermin and was impossible to keep clean. The floor contributed significantly to the Shed’s longevity. The floor is nearly 4 acres and was laid around the poles first. As the poles were put in the 4 foot deep holes, the aggregate concrete was poured around them at about 4 inches thick, this was continued as the Shed was constructed. You can see the result below.

At this point I’d like to cycle back to the poles themselves. The ‘sticks’ that give the Shed its name. As I said they are mountain ash hardwood and unmilled, but they are also largely original. You can see their very tree like nature below.

Some have been shored up with bow trusses, that effectively act as bracing the same way that rigging helps brace a ship’s mast.

The footings have had to be replaced in some

And sadly a few have had to be replaced with metal, for safety reasons. There really aren’t many though.

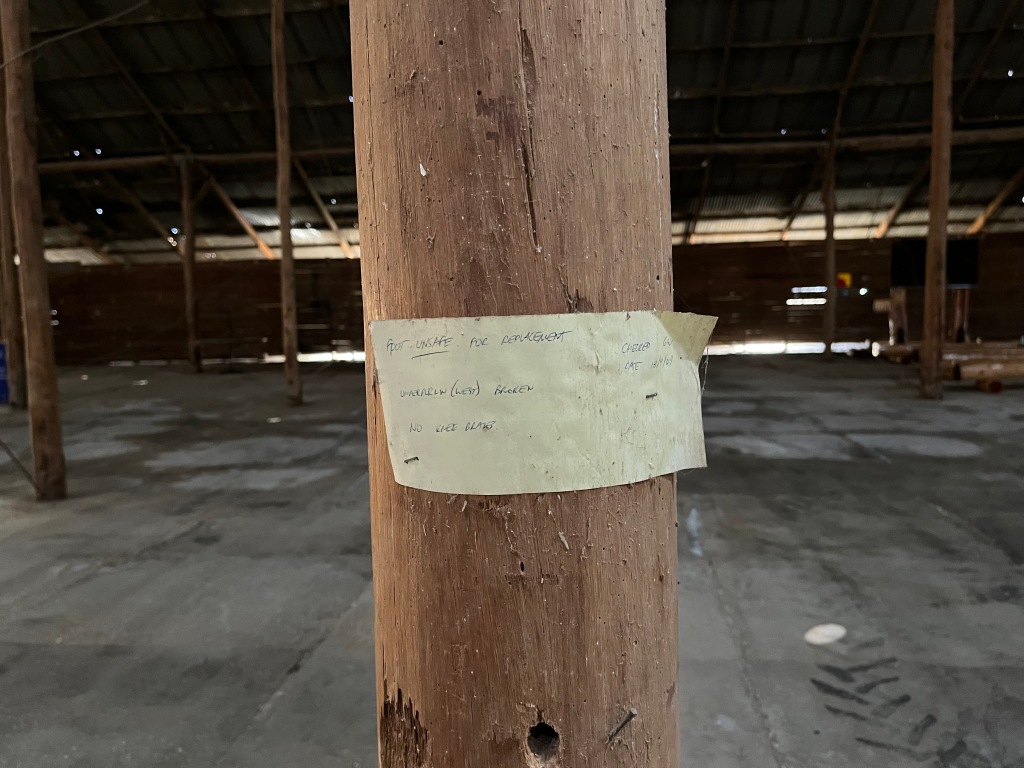

I also really like that you can see the notes on the poles for their maintenance.

Overall the effect is mind-blowing.

It isn’t only the floor and the sticks, the roof is also fairly astonishing

The roof is iron, and covers 1.5 hectares, with over two hectares of actual iron when you take into account the roof slope.

The side walls are also made of iron, with over all nearly five acres of iron going into the Shed. And remember this was WW2 where metal was scarce, which just exemplifies the importance of the Shed. You can see some of the walls below.

That’s the bones of the Shed, how it was built and why. But let’s have the body, how was it used?

The above photo gives you an idea of how the wheat was piled up, but how did it get in there?

It’s actually a fairly simple process. Most of the wheat came in by train, and it was loaded from the sidings. The photo below is the current Murtoa station, you can see the Shed on the far left in the distance.

The grain was loaded on to an elevator which fed the grain into the Shed- you can see the elevator below.

Once in the Shed it was fed onto a conveyer belt that ran the length of the Shed.

Once on the conveyer belt, simple barriers pushed the wheat off into the area of the Shed it was needed. Some people power was required too. There was a worker on the walkway next to the conveyor belt to make sure the wheat was going to where is was supposed to be and one on the floor. The Shed could also be filled by individual farmers from a hopper at the opposite end to the elevator.

The pit was finished in 1947 and extends under the Shed a bit. Farmers could dump wheat either by hand or from a grain truck if they had one, it was then moved into the Shed proper.

Once the grain was in the Shed (it could take an astounding 92000 tonnes) it was largely left alone. It was treated with insecticides by people walking on the top of it when there was an infestation, but it is specifically built with the concrete floor and windows all along the side alleys and ventilators in the roof, to keep infestations to the minimum.

But the wheat didn’t stay in the Shed indefinitely. It was emptied (when needed) with sort of a reversal of the whole process. There were horizontal conveyer belts which helped move the wheat to the side of the building. People were also on hand to operate these belts.

The wheat was conveyed to the south wall, where a belt ran the length of the Shed and trundled it back out of the Shed and on to trains to be sent wherever it was needed.

The wheat in the Shed, as it came from so many sources, was classed and sold as Fair to Average Quality (FAQ).

The Shed was used until 1989, when the Grain Board declared it uneconomical. It was added to the Victorian Heritage Register in June 1990.

So now you know the story of the Stick Shed. Although it is no longer used for the purpose it was intended for, it not only stands as a monument to the history of agriculture in the area, it is a truly spectacular building in its own right.

One thing you do really notices standing in the Shed, is that it is not a silent building. Part of this is because it is still very much in a working agricultural area.

But it is also because the Shed moves, you can hear it shifting and settling, it’s almost elemental.

The Stick Shed is also not the only historically interesting feature of Murtoa. The Murtoa and District Historical Society is housed in the old water tower.

The water tower was built in 1886 for the nearby rail line. It now houses an eclectic museum, the unexpected highlight of which is a remarkable taxidermy collection. It is the work of local minister James Hill and spans 1875-1932. Hill had contacts with missions in Africa, Brazil, India and New Guinea and asked for specimens in return for donations to the missions. He also swapped with other collectors, as far away as Africa. There are over 600 specimens, and it’s one of the largest collections of its type in Victoria outside of Melbourne Museum.

So the Stick Shed does not stand alone. I just wanted to finish with the note that the Stick Shed’s survival, when other large grain stores were demolished long ago, is down to intensive effort by individuals and committees. It has survived, in-spite of the odds against it. And I think we can all agree it was definitely worth saving.

References

Images: The images are all mine, apart from the old image of the full shed, this comes from Culture Victoria. https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/built-environment/wimmera-stories-murtoa-stick-shed-enduring-ingenuity/murtoa-stick-shed-full-of-grain/ and the map, which comes from Google Maps.

Shedding Light: The Murtoa Stick Shed Saga by Leigh Hammerton

Site visit 2022