One of the most interesting heiresses of the period, not in the least because she was married to William Marshal, was Isabel de Clare. Isabel’s marriage to Marshal typified the incredibly important political role that the marriage of these heiresses played. These marriages were not only used as rewards, they were used to elevate men to real positions of power. In some occasions these men could help to change the face of a country, I would argue that Marshal was one of these and his marriage to Isabel was what gave him the status to have a real political affect.

Isabel herself is a little hard to pin down. In essentials she was the perfect medieval wife possessing of great fortune and very fecund, they had ten children, but she makes her own mark in a variety of interesting ways. While the History of William Marshal can not be taken entirely at face value the sentiment that is expressed throughout the work is that Isabel was actively involved in the rule of domains that were essentially hers.

The marriage of Marshal and Isabel de Clare as depicted in the modern Ros tapestry in New Ross in Ireland.

Marshal’s marriage to Isabel de Clare was the most significant elevation in his life. The lands that he gained, the children that he had from the marriage and the qualities of Isabel herself were the building blocks on which Marshal’s status was established. Marriage to Isabel gave Marshal substantial and geographically diverse lands as well as titles and wealth. In comparison, materially, Marshal brought little to the marriage because he was a virtually landless knight who only had one small estate in England and probably the rents of some lands in France. He had amassed considerable wealth however from his prowess on tourney field and he was known and respected by King Richard. Isabel gave Marshal lands in England, Ireland, Wales and what is now France and these lands gave Marshal both wealth and authority.[1] Marshal’s marriage to Isabel mean that he made an indelible mark on her lands, not the least in Ireland. The affect Marshal had on these Irish lands illustrates just how much political change the marriage of an heiress could generate.

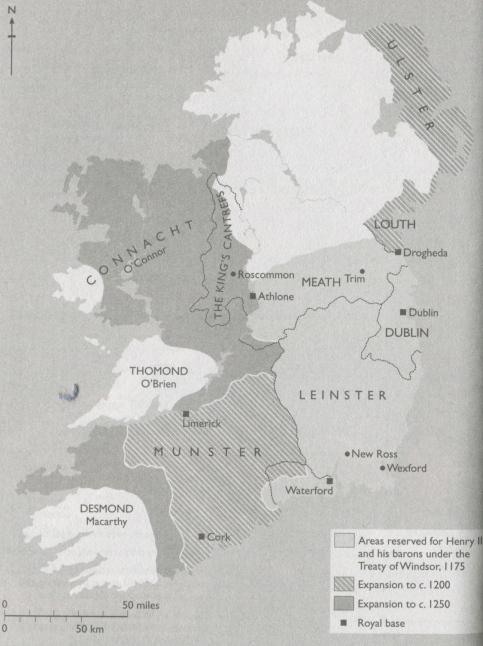

Ireland under the Normans. You can see Leinster, Marshal’s lands, on the right.

David Carpenter, The Struggle for Mastery: Britain 1066-1284, London: Penguin Books, 2004, p. xx.

Isabel’s Irish lands came to her from her father Earl Richard de Clare, known as Strongbow, who had gained them by force, and through her mother Aoife, the daughter and heiress of King Dermot MacMurchada of Leinster who was deposed as king in 1166.[1] Strongbow was a leader in a force spearheaded by English lords who won Leinster back for King Dermot. They were given permission to do so by their king Henry II in a letter recorded by Giraldus Cambrensis c. 1166. This was the beginning of the English occupation in Ireland.[2] The rewards Dermot gave Strongbow in return for his services were recorded in the relatively contemporary poem The Song of Dermot and the Earl: his daughter Aoife in marriage and his kingdom after his death. Dermot died in 1171.[3]

Dermot’s grave in Ferns, Ireland.

Strongbow died in 1176 leaving a son and daughter too young to inherit and so Leinster was in the hands of the Crown until Strongbow’s son came of age. The son, Gilbert, died as a minor in 1185 and thus Isabel de Clare inherited everything. Marshal on marrying Isabel gained lordship of her entire estate.[4] Trouble could be expected from the local Irish population who were not likely to welcome a new overlord. These peoples included the English lords who had been settled there for more than a decade and the original Irish lords. Marshal faced an uphill challenge in controlling and developing Leinster and it was one at which he certainly succeeded

On taking possession of Leinster Marshal sent deputies but did not go himself until c. 1201, and then only for a brief visit. The Irish Annals found in The Chartularies of St Mary’s Abbey in Dublin recorded that Marshal was in Ireland c. 1201.

All that remains of St Mary’s Abbey in Dublin.

They said that he came in a storm and, in thanks to God for his survival on the unforgiving Irish Sea, he founded the abbey of Tintern Parva.[5]

Tintern Parva on the Hook Head Peninsula in Ireland.

Depiction of the near disaster on the Irish Sea from the Ros Tapestry.

Marshal returned to Ireland in c. 1207 and faced rebellion, mainly from Meyler Fitz Henry. Fitz Henry was one of the original settlers, a bastard grandson of Henry I and had been appointed Justiciar of Ireland, ruler in the king’s absence, by King John. He was tenant in chief of some small fiefs, most of which he held from Marshal. Fitz Henry and Marshal were in repeated conflict and King John involved himself in Fitz Henry’s favour. Fitz Henry led many battles against Marshal’s lands both when Marshal was in Ireland and when he was not.[6] As can be seen in two charters from King John in 1216 Marshal ultimately managed to prevail and found his way back to John’s favour with Fitz Henry disgraced. The first granted Marshal Fitz Henry’s fees, a form of rent or tax, in Marshal’s own lands. The second said that if Fitz Henry should die or take the habit Marshal was to receive Fitz Henry’s fees in the Justicary’s jurisdiction, which effectively disinherited Fitz Henry’s son.[7]

As well as exercising control Marshal was responsible for developments such as the port town of New Ross. Marshal began New Ross, which still exists today, in c. 1207.[8] Once it was established, Marshal set about making it a viable port town. When he was back in favour with King John, c. 1212, Marshal negotiated to ensure that shipping could continue through Waterford and onto New Ross. Waterford was the main port and the Crown had controlled it since 1171.[9] Marshal needed his own port and New Ross suited well because of its deep harbour, river access to the heart of Leinster and links with nearby lordships.[10]

The Barrow river in New Ross.

New Ross is only one of the building and consolidation projects that Marshal undertook in his Irish lands during his lordship. He established other towns and also built a number of castles. He made settlements on the edges of nearby counties, retook land that had been previously lost and established monastic foundations and built a lighthouse which still stands today.

Marshal’s lighthouse on the Hook Head Peninsula.

Ferns Castle which Marshal also built.

Marshal also took over lands that had lacked any kind of central authority because the Crown had run them for many years from a distance.[11] Marshal managed to establish a strong and stable lordship, despite the fact that he was so caught up in English affairs. This administrative skill ensured that he maintained his position as Lord of Leinster, as well as his other lands, and that he was sufficiently influential and experienced to become first the Earl of Pembroke, a title which he came to through right of Isabel, under King John in 1199 and then Regent in 1216.

When Marshal married Isabel de Clare he became one of the most influential barons of his time because the marriage laws meant he became ruler of everything that was hers. When it came to marriage, a woman’s lineage, her family and connections, were as important as her lands. In Marshal’s case through Isabel he gained the physical lands themselves but also the eminence of her background as the daughter of an earl and the granddaughter of a King of Ireland.

Lineage and land were not all that Marshal gained from his marriage because the couple also had ten children, five sons and five daughters, all of who survived to adulthood.[12] All five daughters married influential and high ranking noblemen and only the youngest, Joan Marshal, was unmarried when her father died.[13] This gave Marshal alliances in a variety of noble families, another use for heiresses, and helped to give him the support he needed to stay in power even when he was out of favour with King John. It is due to his eldest son William that his memory survives today in such detail because it was he who commissioned the History. Marshal achieved what eluded many prominent landholders of his time because he had five sons thus having multiple heirs. When Marshal died his authority and legacy seemed safe and his position solidified, which must have made reaching the top of his society seem worthwhile because he had been able to protect all his family and to pass on what he created secure in the knowledge of its survival. Success in this time was intended to be dynastic rather than just personal. Unfortunately this was not to come to pass because, although Marshal never knew it, his sons all died childless and his lands were dispersed.[14]

Chepstow Castle which Marshal gained from marriage to Isabel. He also built significant proportions of it.

Children, lineage and land aside, Isabel as a person and the role she played in the marriage and thus in Marshal’s ascent is much harder to define but just as vital and fortuitous. Isabel came to the marriage probably in her late teens while Marshal was in his early forties. Despite the age difference by all accounts she was an active participant in the marriage and in the governing of the lands. If she had not been it is unlikely that Marshal would have succeeded so well in holding together his disparate domains. She was not only his entrée into the high aristocracy, but her support was important to the retention of his authority. There may have been no legal repercussions if Isabel had not supported Marshal, but the people he ruled were her vassals and would have been more likely to rebel against their new untried lord without Isabel’s support.

Marshal trusted Isabel and her abilities enough to leave her in an administrative position in Ireland c.1207 during the fragile military and political situation, when King John forced him back to England. Before returning to England in c. 1207 the History reports that he said to his men.

My Lords, here you see the countess whom I have brought here by the hand into your presence. She is your lady by birth, the daughter of the earl who graciously, in his generosity, enfieffed you all, once he had conquered the land. She stays behind here with you as a pregnant woman. Until such time as God brings me back here, I ask you all to give her unreservedly the protection she deserves by birthright, for she is your lady, as we well know; I have no claim to anything here save through her.[15]

While it is very unlikely that he spoke these exact words the sentiment is clear. Isabel was Marshal’s key to ruling.

Isabel was a potent symbol to Leinster. She was the daughter of the Princess of Leinster and the granddaughter of its last king, which would have pleased the Irish lords. She was the daughter of Richard Strongbow who had been responsible for establishing many of current English lords, or at the least their fathers, in their lands in Leinster and because she was pregnant she represented the future of the lordship. By leaving her behind Marshal had a reasonable chance that many of his lords would cleave to her and thus his cause, which would leave him free to deal with King John.

Isabel proved a very able defender of Marshal and their lands in Ireland. Almost as soon as Marshal left, she found herself embroiled in war and by 1208 she was besieged in Kilkenny castle and “she had a man let down over the battlements to go and tell John of Earley that it was the very truth that she was besieged in Kilkenny.”[16] John of Earley came and Isabel’s men were victorious. It was also Isabel with whom Meyler Fitz Henry first made peace and it was recorded in History that “he [Fitz Henry] had made peace first with the countess and then with the earl’s men, and … he had given his son Henry as a hostage for his inheritance.”[17] Isabel was very much in command of the defence of her lands even if she could not physically lead men. Isabel was a unifying figure because of her lineage and without her presence in Ireland and her willing participation Marshal could have easily lost Ireland while he was trapped at John’s court.

Kilkenny Castle as it is today.

Defending her lands was not Isabel’s only involvement because she was also engaged in their creation and improvement. Marshal took the fact that his only claim to the lands was through Isabel very seriously because he made many developments in Leinster with charters that had Isabel’s ‘counsel and consent’ recorded on them.[18] According to Cóilín Ó Drisceoil there is a tradition that Isabel had been heavily involved with making the decision to locate the foundation of the town of New Ross on the Wexford bank of the Barrow River. This was not necessarily the most practical bank on which to build a town, as it was steep and required the building of one of the longest bridges in medieval Ireland. It was perfect however from a political point of view because Wexford was the centre of the former Kingdom of Leinster.[19] The earliest written mention of the tradition of Isabel’s involvement in New Ross’s foundation was in the 1607 work Britannia by William Camden.[20] Isabel understood the political imperatives in building a new city and made sure that they were carried out correctly. She also helped to ensure that Marshal remained lord of all their other lands as well because unlike other noble wives she commonly travelled with him throughout their domains and was involved in their governance. She was the symbol by which Marshal governed as well as an active participant.

St Mary’s Abbey which Marshal and Isabel built in New Ross.

Marshal and Isabel’s match seems to have become one of love. This was exemplified by the way Isabel behaved during and after Marshal’s prolonged death. Marshal first began to fall ill around the end of January 1219 and it took him until midday on May 14th 1219 to actually die.[21] A very moving picture of Isabel just after his death was painted in History “whilst mass was being sung it was observed that the countess could not walk without danger of coming to grief, for her heart, body, her head and limbs had suffered from her exertions, her weeping and her vigils.”[22] This was a final testament to a woman who had stood strongly by Marshal throughout much of his life and his protracted death and had continued to love him. Isabel died only a year later and was buried at Tintern Abbey in Wales.

The Temple Church in London where Marshal was burried and his effergy.

Tintern Abbey in Wales where Isabel was burried, no trace of her burial remains.

Marshal was given Isabel as a reward and as a way of binding a skilled warrior and an admired man to the new King Richard I in 1189. The authority bestowed on him by this land and the wealth he acquired through marriage meant that he had the ability to make an indelible mark on England. When King John died in 1216 he left a country in turmoil with many of the country’s barons in rebellion. The then approximately 70 year old Marshal was made Regent for the nine year old Henry III and under his direction the country was brought back from the brink and Henry III’s kingship saved. The situation was dire enough to prompt Marshal to declare, according to the History, when he assumed the Regency that “if all the world deserted the young boy, except me, do you know what I would do? I would carry him on my shoulders and walk with him thus,” “ and never let him down from island to island, from land to land.” [23] Marshal was the head of the government who defeated the rebellious barons and the French Prince Louis, later Louis VIII, who was the barons’ candidate for the throne of England.[24] Marrying wards to loyal followers as rewards was a long held practice and one that continued. Much of the time it had little overall effect, however on occasion it elevated a man such as Marshal to a prominent position in society which enabled them to have a far-reaching consequences on the political situation, often in multiple countries.

This will for the moment be the end of my series of noble marriages. I may come back to it at a later date.

All the photos, obviously baring the map at the beginning, are mine.

[1] Catherine A. Armstrong, William Marshal Earl of Pembroke, Kenneshaw: Seneschal Press, 2006, pp. 60-61.

[2] Giraldus Cambrensis, The Conquest of Ireland, (trans.) Thomas Forster, Cambridge: Parenthesis Publications, 2001, p. 13.

[3] Anonymous, The Song of Dermot and the Earl, (ed.) & (trans.) Goddard Henry Orpen, Oxford: the Clarendon Press, 1892, pp. 19-27.

[4] Armstrong, Earl of Pembroke, p. 77.

[5] John T. Gilbert, (ed.) Chartularies of St Mary’s Abbey Dublin with The Register of its House at Dunbrody and Annals of Ireland, Volume II, London: Longman and Co, 1884, pp. 307-308.

[6] Sidney Painter, William Marshal: Knight Errant, Baron and Regent of England, Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1933 pp. 145-146.

[7] H.S Sweetman, (ed.) Calendar of Documents, Relating to Ireland, 1171-1251, London: Longman and Co, 1875, p. 106.

[8] Cóilín Ó Drisceoil, “Pons Novus, villa Willielmi Marescalli: New Ross, a town of William Marshal” in John Bradley & Cóilín Ó Drisceoil, (eds) William Marshal and Ireland, Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 8-9. A note about this particular text. I am unsure what is happening with the publication of this text. I was very kindly sent advanced chapters and given clear permission to use them for reference in my thesis. I feel that as the sections of this post in which I am using this information are almost verbatim from my thesis that this permission should extend to this post. I am endeavouring to discover what has happened to the publication of this book, but it seems as if it may have actually fallen through, I’m not sure. I still think the information is worth including though.

[9] Sweetman, (ed.) Ireland, p. 99.

[10] Ó Drisceoil, “New Ross” in Bradley & Ó Drisceoil, (eds) William Marshal and Ireland, pp. 10-11.

[11] Adrian Empy, “The Evolution of the Demesne in the Lordship of Leinster: the Fortunes of War or Forward Planning?” in Bradley & Ó Drisceoil, (eds) William Marshal and Ireland, pp. 36-38.

[12] T.L Jarman, William Marshal: First Earl of Pembroke, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1930, p. 99.

[13] Anonymous, History of William Marshal, (ed.) AJ. Holden, (trans.) S. Gregory & (notes.) David Crouch, Volume II, London: Anglo-Norman Text Society, 2002. pp. 410-411.

[14] Matthew of Westminster, The Flowers of History: Especially as they Relate to the Affairs of Britain from the Beginning of the World to the year 1307, (ed.) & (trans.) C.A. Yonge, Volume II, London: AMS Press, 1968 , pp. 257-258.

[15] History, Volume II, pp. 177-179.

[16] History, Volume II, p. 193.

[17] History, Volume II, p. 195.

[18] Ó Drisceoil, “New Ross” in Bradley & Ó Drisceoil, (eds) William Marshal and Ireland, pp.11-12.

[19] Ó Drisceoil, “New Ross” in Bradley & Ó Drisceoil, (eds) William Marshal and Ireland, pp. 9-11.

[20] William Camden, Britannia, (trans.) Phillemon Holland, at http://www.philological.bham.ac.uk/cambrit/irelandeng1.html#ireland1, accessed 05/12/14.

[21] David Crouch, William Marshal, Knighthood, War and Chivalry, 2nd ed, London: Pearson Education, 2002, pp. 138-140.

[22] History, Volume II, p. 453.

[23] History, Volume II, p. 287.

[24]D.A Carpenter, The Minority of Henry III, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990, pp. 17-64.