Welcome to another iteration of Ragbag On Road. In this edition, you find me on the incredible Silo Art Trail in Western Victoria. Introduction below.

So, in this post I’m going to take you on a tour of the Silo Art Trail, its history and some of the history of the towns and the silos themselves. This post is part of a longer series, which also explores the integration of art and history. You can see more at the links below:

I won’t be including every piece of silo art in Victoria- as it has spread well beyond the original trail. But I have covered the original trail, with its newest additions.

Before I go anything further- I would like to acknowledge the First Nations people on whose lands these silos were built and art work created. A lot of the history of these towns I’ll be discussing is rooted in pioneers and Europeans discovery. For First Nations people, this is a history of dispossession and colonisation. These lands were not unoccupied with western people moved into them.

But what is the Silo Art Trail?

The Trail started with the painting of one silo in Brim in 2016. The premise was a local art project, with the collaboration of both the local community and an artist, to paint the silo to reflect the community. The project was so popular that the Silo Art Trail was conceived and now stretches over 600 km, linking small towns across the Wimmera and Mallee regions of Victoria and creating the largest outdoor gallery in Australia. I’d heard of the Silo Art Trail, but when I was in the Wimmera in August I was unexpectedly impressed by both the sheer grandeur and size of these art works (some are as much as 30 m high) but also how reflective of the local communities they really are. Each artist (and every silo is done by a different artist) worked with, and in many cases lived with, the local community to create something that helps to tell their story. Following the Trail is also a great opportunity to explore these fascinating little towns. So as well as the silos themselves, I’ll be including something about the local history of each town.

But to begin at the beginning…

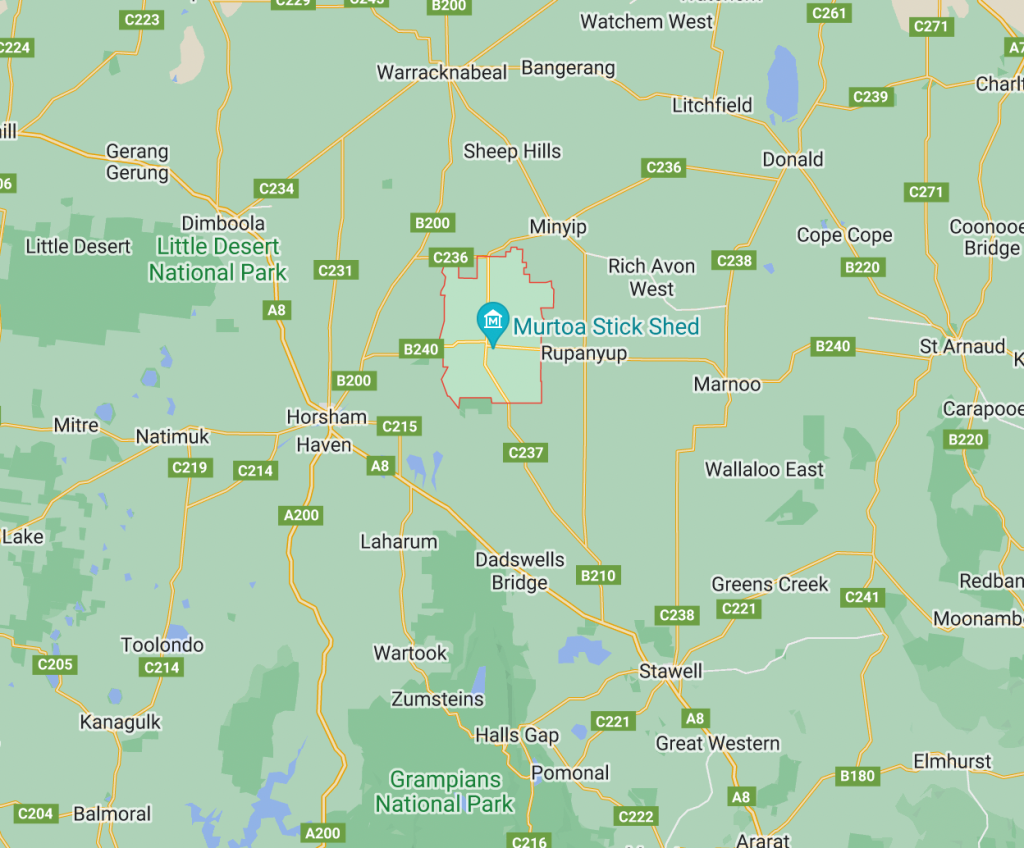

Below you can see the map of the Silo Art Trail

And to give you an idea of the landscape of the Malle and the Wimmera- you can see some photos below.

As you can see- it’s a land of big skies, agriculture and desert. There was a lot (and I mean a lot) of water when I was exploring, due to an unusually heavy rainfall. Though the large body of water you can see is Lake Tyrell (more on that later).

So the silos are- mostly- working agricultural sites. I’ll be leading you through them, much as I visited them because following the trail itself is half the fun.

So…

St Arnaud

The St Arnaud silos were painted in 2020 by Kyle Torney. Torney is a St Arnaud’s local and spent 200 hours on the work which is entitled ‘Hope’. It depicts a miner hoping to find gold, as his wife hopes to find the food to feed them all and the hope of the future of their child. The silos themselves are still commercially run and owned by Ridley Agricultural Products.

St Arnaud actually began life as a gold mining town. In 1855 a group of prospectors travelled to the area in search of a ‘new Bendigo’. And on a knoll in what became St Arnaud they found gold. The town grew rapidly with the registration of the claim, with people coming in from all over the world. Which can be seen in the Chinese garden which is part of the town, built in memory of the Chinese miners who came seeking their fortunes in St Arnaud. You can see it below

Over 20 000 people came to the goldfield that was (at the time) only 40 acres, much of it without any alluvial gold. Most were disappointed, but as the gold field was expanded, some were successful and these prospective miners needed supplies and thus the town began to grow.

Rupanyup

The Rupanyup silo was painted by Julia Volchkova in 2017. It’s reflective of the young people of the Rupanyup area, and their commitment to community through sport. The images are of locals Ebony Baker and Jordan Weidemann. Volchkova wanted to celebrate the community and the hope, strength and camaraderie of their young people. The silos belong to Australian Grain Export and are still in active use.

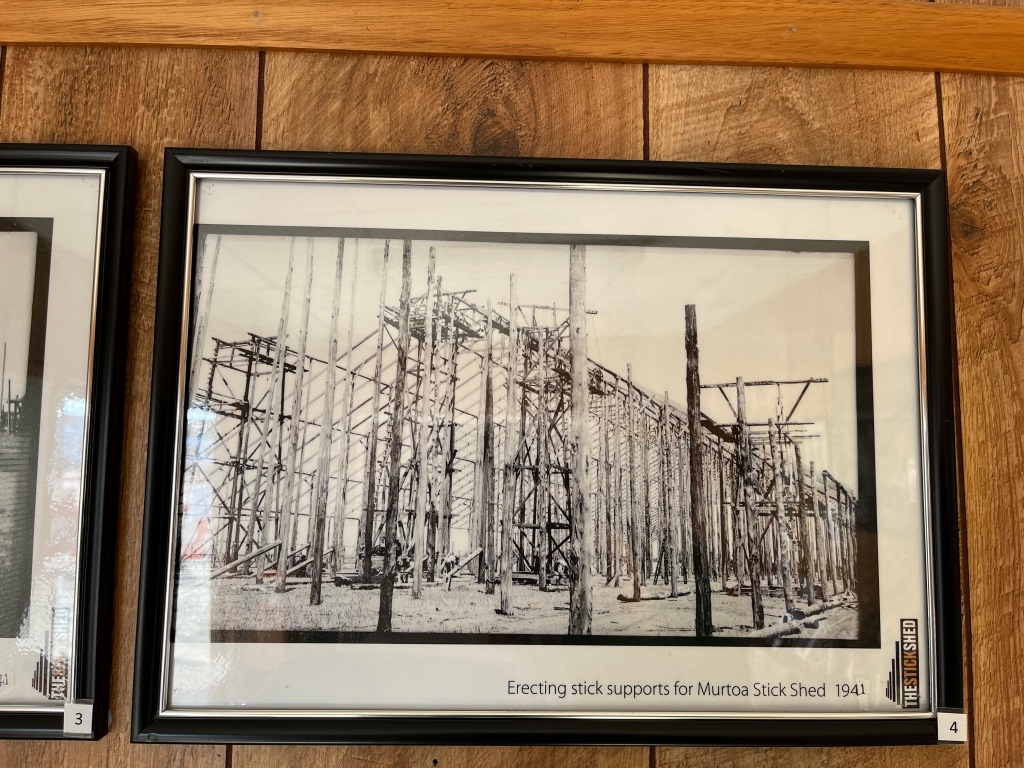

Another piece of fascinating Wimmera history is nearby Rupunyup too. The Murtoa Stick Shed (which you can see in the photo below) is an amazing survival of World War II grain surplus storage. I have written an earlier post about it too- which you can see here: https://historicalragbag.com/2022/08/15/ragbag-on-road-murtoa-stick-shed

The town of Rupanyup itself has its roots in agriculture. Settlers began to move into the area in the 1870s, taking advantage of the rich soil and flat plains to plant crops and run livestock. They also worked hard to fence what they saw as virgin territory as they laid claim to these new lands. It is worth pointing out again, that the lands were not in any way unoccupied. The settlers lived a remote existence, troubled by the lack of reliable water sources as well as the tyranny of distance. But eventually a town grew up, and Rupanyup remains very much an agricultural community today.

Sheep Hills

So we reach the silos featured in the video. Sheep Hills are GrainCorp Silos, which were built in 1938 and were painted in 2016 by Matt Adnate. Adnate wanted to illustrate the local First Nations young people and their connection to elders, community and country. He worked closely with the Wergaia and Wotobaluk communities and painted on the silo are Wergaia elder Uncle Ron Marks and Wotobaluk elder Aunty Regina Hood. The two children are Savannah Marks and Curtly McDonald.

The night sky represents elements of local dreaming and, overall, the silos tell the story of the transfer of knowledge from one generation to the next.

Sheep Hills itself is a farming community. By 1900 there was a thriving town, with a contemporary map showing: a school, four churches, sale yards, cemetery, dressmaker and boot maker, banks, blacksmith, green grocers, hotels, timber yard, butchers and the creamery. It’s also adjacent to Sheep Hills Station which was bought by the McMillan brothers in 1855 and in 1860 George McMillan built a homestead which he called Kingungwell (a name he apparently derived from the ‘king’ of the local first nations people- Aungwill). The homestead was a lavish affair, so much so that many local people called McMillan mad for doing things like: building entirely from Oregen timber and installing cedar cupboards, and constructing a tower and a croquet lawn. The homestead was demolished after WWII. Today Sheep Hills is a much quieter affair- but you can see the mechanics’ institute below.

Brim

The silos that started it all. Guido Van Helten’s multigenerational depiction was completed in 2016. Van Helten wanted to highlight the generations, both male and female, who have farmed this land and will farm it into the future. By rendering the figures as not entirely substantial Van Helten wanted to explore the shifting ideas of community identity and the difficulties faced by rural communities, especially in the face of climate change. The final message really hit home for me, as I was travelling through the area in a time of unprecedented, unseasonable rain levels. The interest that this silo sparked, was the flame that lit the Silo Art Trail, drawing people from all over the world to the Wimmera and Mallee regions.

Van Helten specialises in the painting of everyday figures in forgotten places and won the Sir John Sulman prize from the Art Gallery of NSW in 2016 for his work in Brim.

Brim itself is a rural community- with deep roots in community organisation. With active local sport clubs and community groups. One of the interesting historical markers just up the road is the netting fence which was erected in 1885 to stop rabbits and dingoes overrunning agricultural land to the south. The fence stretched to the South Australian border and the marker can be seen below.

Rosebery

The Rosebery Silos were painted by artist Kaff-eine in 2017. The silos themselves are GrainCorp and date back to 1939. Before she started painting, Kaff-eine spent time with Rone at the Lascelles silos (coming up soon) and touring the local towns and getting to know the communities. Depicted in the art work is firstly- the sheer grit and determination of the young female farmers of the region as they face fire, flood and drought, symbolising the future and, secondly, the close friendship between a farmer and his horse- symbolising the connection between the humans and the animals of these regional communities.

Rosebery itself is named after Archibald Philip Primrose the 5th Earl of Rosebery who became Prime Minster of the UK in 1894. Settlers arrived in the area from the mid 1800s and by 1895 Rosebery had a school, butcher, churches, greengrocer, undertake, saddler, foundry, billiard room and a wine saloon. Today Rosebery is a much quieter town, but it is still the heart of a strong farming community.

Watchem

Watchem is one of the newest additions to the Silo Art Trail completed by Adnate and Jack Rowland in March 2022. The artwork depicts two renowned harness racers- Ian “Maca” McCallum and Graeme Lang. McCallum drove 16 winners in one program in Mildura in 1985, making him a local legend, and Lang was sport’s best from the late 1960s onwards and trained the legendary horse Scotch Notch. The silo is currently in the middle of the disused basketball court- but will be moved to the main street.

Watchem itself has a slightly ghostly presence. It’s quite clear that it was originally a much larger town. Along with the abandoned basketball court, there is an abandoned oval, school and train station, as well as a very impressive church (not abandoned).

Watchem has been the victim of the need for more land to make farming profitable which has reduced the number of people in these off the highway settlements. Also as the population has continued to age, the amount of people living in Watchem has continued to shrink. The situation is was not helped by the drought years, which saw Watchem Lake (which attracted campers) dry up. Watchem began as a community serving settlers setting up farms and livestock runs. No one really knows exactly where the name came from, it was thought that it might have been a First Nations word, but no link had been found.The first official mention was in 1864 when the Land Board instructed the Surveyor to “lay off a direct line to Watchem.” Today there is still a community at Watchem, one that is proud of its heritage and hopefully the Silo Art Trail can help being people back to the town.

Nullawil

Nullawil silo was painted in 2019 by the artist Smug. Smug painted the work over two weeks in difficult wet and windy conditions. Made especially hard by the fact he was working on a cherry picker (as did most of the artists). You can get a feel for what the conditions might have been like when you look at the carpark during my visit.

Smug’s work depicts a farmer and his faithful kelpie. The work doesn’t depict a specific person, rather an amalgam- standing in for farmers across the region and their connection to their animals and the land.

The silos themselves were built in early 1940s and remain operational today along with the railway line which runs up to them.

Nullawill itself began as pastoral leases in 1849, the town now stands on what was the junction of the Knighton and Lansdowne runs. It was later divided into lots of 500-600 acres and they were leased for 2 pounds a year in 1891. The town grew out of the settlers moving to the areas to take up these leases. It was proclaimed a township in 1898 and you can see its immaculately kept central part below.

Sea Lake

Sea Lake’s silos were painted by Travis Vinson and Joel Fergie in 2019. The artwork is entitled ‘The Space In Between’ and tells the story of a young girl swinging from a eucalyptus over Lake Tyrell. They also link to the First Nations knowledge of astronomy, that has been recorded in detail in this area. Lake Tyrell is a special spot for astronomy and stargazing due to the lack of light pollution from nearby towns and the completely clear access to the sky (when there aren’t any clouds-which there were the night I was there). The art work also pays homage in colour to the vibrant sunrises and sunsets the region is known for.

The town of Sea Lake takes its name from its proximity to Lake Tyrell. Lake Tyrell’s name comes from the First Nations word ‘direl’ meaning sky. And sky is what you get. Lake Tyrell is the largest inland salt lake in Victoria- covering an insane 20, 800 hectares. It has been used for commercial salt production since the 1800s and is still today (though much more sustainably). The lake itself is thought to be the remains of when the seas rose many thousands of years ago and flooded what is now the Murray-Darling basin. When they retreated, Lake Tyrell was left behind. The lake is known for its reflective surface, mirroring the sky back up. When I visited it was very full of water and windy, so while I was able to appreciate the vastness and its beauty, especially with how much of the sky you can see unobstructed by land, I didn’t see the mirror affect.

Sea Lake was formed both from use of Lake Tyrell, but also from Tyrell Station which ‘taken up’ in 1847 by W.E Standbridge. It remains an agricultural community, with close ties to the lake.

Woomelang

I’m going to depart a little from my format so far for this section, because Woomelang does not have one large silo painted. They elected to have eight grain bins painted by different artists instead, creating their own little silo art trail, within the Silo Art Trail. So i’m going to go through each grain bin individually. They all reflect some of the local wildlife and were painted in 2020.

This bin was painted by Bryan Itch and depicts the pygmy possum. Pygmy possums are tree dwelling marsupials, who are nocturnal and so small they are very hard to spot. The main threat, even above introduced predators, is land clearance for agriculture. Itch says he chose the pygmy possum because he loves painting the hidden beauty of small things.

This bin was painted by Andrew J Bourke and depicts Rosenberg’s heath monitor, a terrestrial predator who lay their eggs in termite mounds and eat carrion, small birds, eggs, small reptiles and insects. Like the pygmy possum their main threat is land clearance. Bourke chose the heath monitor because they are inquisitive, confident and extremely intelligent.

This bin depicts the western whipbird and was painted by Chuck Mayfield. The whipbird, has a distinctive call like a squeaking gate- they have sadly been almost wiped out from the Mallee. Mayfield painted the whipbird to give it a bigger stage as so few people will have seen one in real life.

This bin depicts the spotted-tailed quoll and was painted by Kaff-eine who also did the Rosebery Silo. The spotted-tailed quoll is a mostly nocturnal predator who mainly hunts medium marsupials. Like the other animals so far, they are at great risk from habitat fragmentation. Kaff-eine chose the spotted-tailed quoll because she wanted to paint it with humans to illustrate the both the playful nature of the quolls but also the important human role in protecting the quolls.

This bin depicts the malleefowl. A uniquely Mallee bird, which is a ground-dwelling, shy, and seldom seen bird which mates for life. Artist, Mike Makatron, wanted to depict the life cycles of the malleefowl.

This bin depicts the lined earless dragon, a small mottled lizard who communicates with head nods and pushups. The dragon was painted by artist Goodie, who chose it because she has always loved reptiles, especially painting their scaled texture and she thought the dragon would sit well on the bin.

This bin depicts the Mallee emu wren, a diminutive bird native to the Mallee. It was painted by Jimmy Dvate.

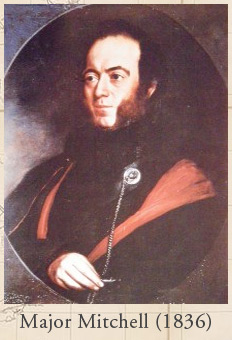

This bin depicts both the Major Mitchell’s cockatoo and the south-eastern long eared bat. The cockatoo was painted by Bryan Itch and the bat by Chuck Mayfield. Major Mitchell’s cockatoo is an iconic Australian bird, now in decline (again largely due to habitat destruction). Itch jumped at the chance to paint it, to capture its feathers emblematic of the dusky Australian sunset. The bat is a micro-bat active at night, hunting with echo-location and roosting during the day in crevices and under tree bark. Mayfield wanted to paint the bat on such a large scale as they are so elusive to find.

So that’s Woomelang’s silos- the town itself? The earliest map dates to 1899 and by this time the town had a railway line, a hotel, a store, churches, and a school was being built. Today it remains a mid sized rural town.

Lascelles

Lascelles was painted in 2017 by Rone- who I have written about briefly in my look at his transformation of the Flinders Street Ballroom in 2022. You can read that here:

https://historicalragbag.com/2022/11/28/flinders-street-ballroom-part-2/

The GrainCorp silos at Lascelles were built in 1939. Rone worked specifically with the colours of the silos themselves to make it look like the figures are emerging from the concrete. Depicted are Geoff and Merrilyn Horman who are part of a farming family who have farmed the land for four generations.

Lascelles was originally called Minapre but the name was changed to honour of EH Lascelles of Messers Dennys, Lascelles, Austin and Co. from Geelong, who were seen as a mainstay of the local community. In 1911 an article called “the Progress of Lascelles” highlighted the town’s rifle club, theatre club, hotels, station, school, churches, banks, races, stores, sale yards, livery stables and coffee palace. Like most of the other Mallee towns discussed it rose to support the local farms and community.

Patchewollock

Painted in 2016 by Brisbane artist Fintan Magee- the 1939 GrainCorp silos show local man, and grain farmer, Nick “Noodle” Hulland. Magee lived at the local pub while painting and chose Hullund because he typified the no-nonsense hard working farmers and spirit of the region. He also had the tall and lanky build to fit well on the 35m high silos. As he squints into the distance, he is looking at the challenges of the life of a Mallee-Wimmera farmer.

Patchewollock itself was one of the, comparatively, later subdivisions of the Mallee lands. In 1910 the first areas of the Patchewollock district were made available for selection. A total of 55 blocks were on offer and the cost of water supply and clearing roads was added to the cost of the blocks. There were 240 applicants for the 55 blocks who had to go before a land board and explain why they thought they were eligible to be selected.

The name comes from two First Nations words putje meaning plenty and wallah meaning porcupine grass. So that gives you an idea of the landscape the first selectors were seeing.

Albacutya

Albacutya is one of the newest additions to the Silo Art Trail. It was painted by Kitt Bennett in 2021. He wanted to tell a story of growing up in the country. The boy depicted is the son of the owner of the silos and the woman is yabbying, a common pastime in Bennett’s own country childhood. The vibrant colour is partly in homage to the nearby town of Rainbow. Albacutya silos themselves are very remote, you can see the view opposite in the image below.

But the community of Rainbow is about twelve km away and it was this community that Bennett took his inspiration from. Rainbow itself is vibrant agricultural hub. The name comes from the hill that was covered in colourful wildflowers in springtime. It was originally called Rainbow Rise, but when the town was surveyed in 1900 it was shortened to Rainbow. You can see it in the photos below.

The name Albacutya comes from the nearby Lake Albacutya- which is one of Victoria’s largest ephemera lakes.

Arkona

Arkona is very newly finished- hence the awkward photo because it is on the edge of the highway on the edge of Dimboola with no signs or parking. It has been painted by Smug and is a photo-realistic portrait of local legend Roy Klinge who died in 1991. You can see Dimboola Court House- home of the Dimboola Historical Society in the photo below.

Goroke

Finished in 2020 the Goroke GrainCorp silos were painted by Geoffrey Carran. The word goroke means magpie in local First Nations language- so it was a natural choice for the artwork. He worked closely with the local community to decide what else to include and settled on the the kookaburra and galah- in front of a typcial West Wimmera landscape.

Goroke is the gateway to the Little Desert National Park. The first official selector arrived in the area in November 1874 with the lease of Allotment 1 of the Parish of Goroke for 192 acres. The town sprang from this. The rail line extension in the 1890s greatly helping its foundation. Today you can see the remains of Goroke’s 19th and 20th century heritage throughout the town.

Kaniva

We have reached the end of the trail. Kaniva is only a short distance from the South Australian border. The GrainCorp Silos were painted by David Lee Pereira in 2020. The Australian hobby bird (a type of falcon) and the plains sun orchid and the pink sun orchid (which generally only open on humid days) shine as examples of the desert flora and fauna surrounding Kaniva.

Kaniva itself is a border town, and that is the key origin of its foundation. Today as well as the silos it is home to an amazing sheep art trail, which encompasses sheep painted by the local community organisations. You can see them below.

And that brings me to the end of the Silo Art Trail. I hope you have enjoyed the journey along they way. And stayed tuned for future additions of Ragbag on Road.

I write this blog for free- but it isn’t free to run. If you are able to, I’d really appreciate it if you can make a small donation below to its upkeep.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyReferences:

http://siloarttrail.com/home/#

https://starnaud-siloart.com.au/

https://www.australiansiloarttrail.com/

Back to Goroke: April 20-24 1973: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=15158

Patchewollock and District: A history: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=13426

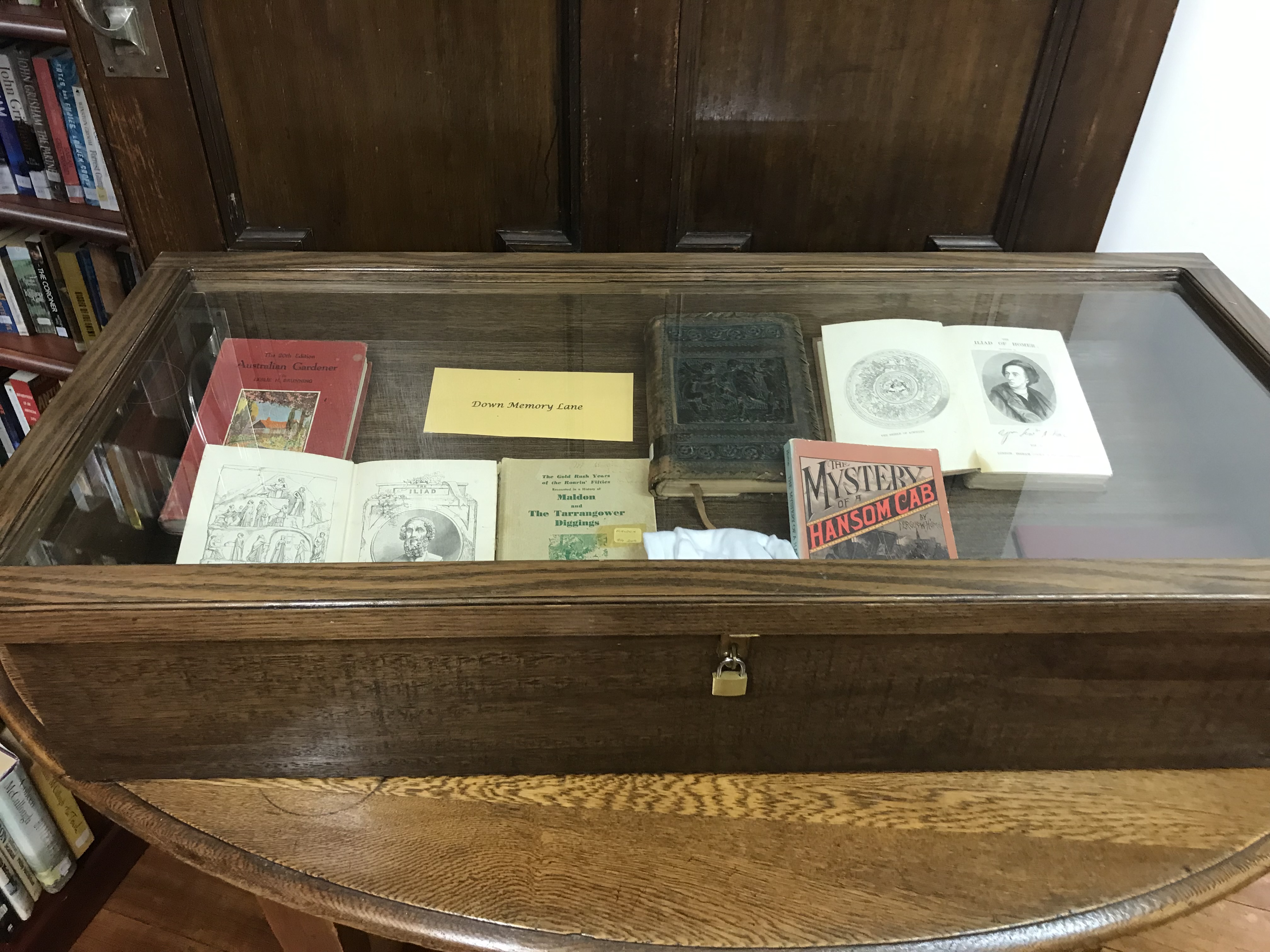

Land Worth Saving: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=17895

Then Awake Sea Lake: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=33765

Nullawil: A folk history: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=17541

The Pioneers and Progress of Watchem: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=6252

Of J.K.M: An autobiography: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=17814

Brimful of Community Spirit: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=4685

Sheep Hills: Stories from past and present residents and other things of interest: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=33259

Rupanyup: https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=21563

Track of the Years: The story of St Arnaud https://library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=18840

Site visits 2022

All the photos are mine.

The stain glass window dedicated to St Thomas also carried a dedication for the A’Beckett family on its base

The stain glass window dedicated to St Thomas also carried a dedication for the A’Beckett family on its base The A’Becketts were a prominent district family and the font is also dedicated to one of their number.

The A’Becketts were a prominent district family and the font is also dedicated to one of their number.

The Mechanics’ Institute dates to 1905, but the current building was built in 1942. The hall was used for everything from ANZAC celebrations to rollerskating. The hall burnt down in 1940 but it was rebuilt, as you can see it today, by 1942. The new building is built in greek revival style and is under the ownership of the council. Today it is used for everything from tai chi to playgroups.

The Mechanics’ Institute dates to 1905, but the current building was built in 1942. The hall was used for everything from ANZAC celebrations to rollerskating. The hall burnt down in 1940 but it was rebuilt, as you can see it today, by 1942. The new building is built in greek revival style and is under the ownership of the council. Today it is used for everything from tai chi to playgroups.

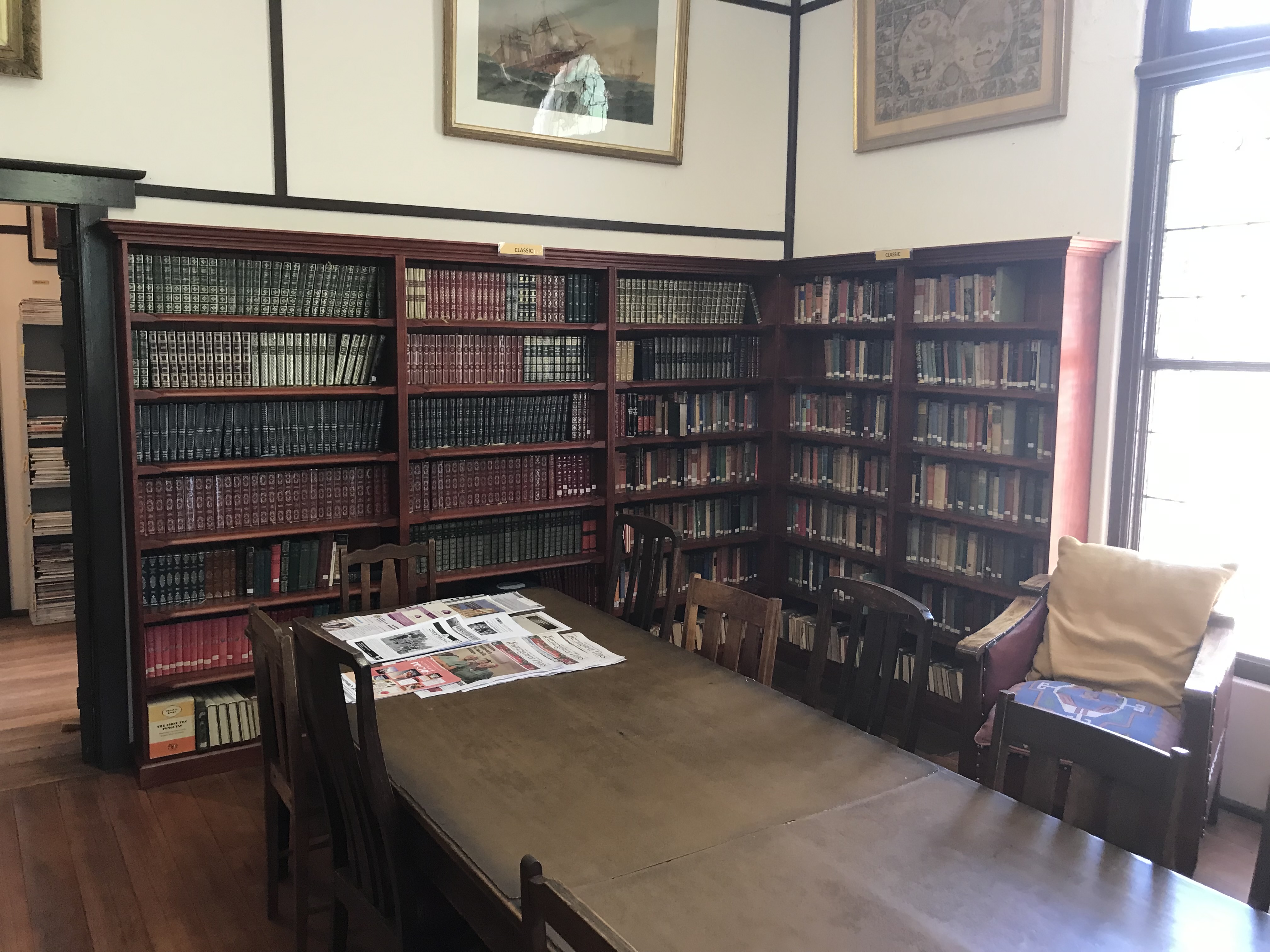

The Institute was established in 1886 and the current building dates to the 1920s. Glengarry began as a library and was much used with hundreds of people visiting the library every year in the 1800s. When the new hall was opened in 1920, it was moved across the road, it was used as a library, a picture theatre, and by many local organisations. The hall had reached a fairly degraded state, on the outside, by 2013 and funding was raised to restore the outside including the hall roof which was in a perilous state. It is still used extensively by the community today.

The Institute was established in 1886 and the current building dates to the 1920s. Glengarry began as a library and was much used with hundreds of people visiting the library every year in the 1800s. When the new hall was opened in 1920, it was moved across the road, it was used as a library, a picture theatre, and by many local organisations. The hall had reached a fairly degraded state, on the outside, by 2013 and funding was raised to restore the outside including the hall roof which was in a perilous state. It is still used extensively by the community today. The Longwarry Public hall, formerly Longwarry Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library, was established in 1886, and the first building built in 1889, though the current building dates mainly to the 1950s. Longwarry operated as a free library and lecture hall as well as being the home of the local brass band and health centre in the 1800s and early 1900s. The hall burnt down in the 1950s and the hall you see today was constructed, it was opened in 1953 with additions in the 1960s. In 2009 it was significantly upgraded including a new roof. It is still used by many community groups and an old time dance has been running every Monday evening and every fourth Saturday since, roughly, 1900.

The Longwarry Public hall, formerly Longwarry Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library, was established in 1886, and the first building built in 1889, though the current building dates mainly to the 1950s. Longwarry operated as a free library and lecture hall as well as being the home of the local brass band and health centre in the 1800s and early 1900s. The hall burnt down in the 1950s and the hall you see today was constructed, it was opened in 1953 with additions in the 1960s. In 2009 it was significantly upgraded including a new roof. It is still used by many community groups and an old time dance has been running every Monday evening and every fourth Saturday since, roughly, 1900.

Founded in 1860 and the current building dates to 1865. A library was functioning in Belfast, as it was then known, as early as 1856 but an institute wasn’t officially formed until 1860. In 1864 land was granted by James Atkinson to build a library for Belfast and it has remained in the same position since it was opened in 1865. The Lecture Hall next door was also opened at roughly the same time. The library is now used as the public library, after 120 years of independent operation it joined the Corangamite Shire libraries in 1981. The lecture hall is used by lots of community groups including the local theatre group and the spring festival.

Founded in 1860 and the current building dates to 1865. A library was functioning in Belfast, as it was then known, as early as 1856 but an institute wasn’t officially formed until 1860. In 1864 land was granted by James Atkinson to build a library for Belfast and it has remained in the same position since it was opened in 1865. The Lecture Hall next door was also opened at roughly the same time. The library is now used as the public library, after 120 years of independent operation it joined the Corangamite Shire libraries in 1981. The lecture hall is used by lots of community groups including the local theatre group and the spring festival.

The Stratford Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1866 and the current building was constructed in 1888. When it was originally founded Stratford lapsed very quickly and another attempt to form a Mechanics’ Institute was tried in 1874, which didn’t work either. However, by 1882 a committee was formed and the library was set up in the shire hall and books bought. By 1888 they’d built the existing hall. In the 1950s a spectacularly ugly addition was built on the beautiful 1800s facade. It mainly housed toilets. In the early 2000s, through fundraising and government grants, the hall was restored to its former 1800s glory. It is run by an active committee and is the home to many local events, including the parts of the Stratford Shakespeare festival.

The Stratford Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1866 and the current building was constructed in 1888. When it was originally founded Stratford lapsed very quickly and another attempt to form a Mechanics’ Institute was tried in 1874, which didn’t work either. However, by 1882 a committee was formed and the library was set up in the shire hall and books bought. By 1888 they’d built the existing hall. In the 1950s a spectacularly ugly addition was built on the beautiful 1800s facade. It mainly housed toilets. In the early 2000s, through fundraising and government grants, the hall was restored to its former 1800s glory. It is run by an active committee and is the home to many local events, including the parts of the Stratford Shakespeare festival.

Port Fairy is a town in Western Victoria that was founded as a town in 1843. There were settlers in the area before this date, and the current name for the town comes from the ship the Fairy which is believed to have arrived in the area in c.1828. The area was also regularly visited by whalers and sealers. The date of 1843 comes from the special survey which was granted to James Atkinson at that time. The special surveys were a system where the government of the Colony of New South Wales was able to control ownership of the land in the Port Phillip District. This was well before federation of Australia as a country in 1901, but also before Victoria became a colony independent from New South Wales which happened in 1851. The basic premise behind the special survey system was to stop squatters just claiming land, because when they did there was little ability to regulate it and there was no fee for the government.

Port Fairy is a town in Western Victoria that was founded as a town in 1843. There were settlers in the area before this date, and the current name for the town comes from the ship the Fairy which is believed to have arrived in the area in c.1828. The area was also regularly visited by whalers and sealers. The date of 1843 comes from the special survey which was granted to James Atkinson at that time. The special surveys were a system where the government of the Colony of New South Wales was able to control ownership of the land in the Port Phillip District. This was well before federation of Australia as a country in 1901, but also before Victoria became a colony independent from New South Wales which happened in 1851. The basic premise behind the special survey system was to stop squatters just claiming land, because when they did there was little ability to regulate it and there was no fee for the government.

He died in 1862 at the age of 40 and the tomb reads:

He died in 1862 at the age of 40 and the tomb reads:

There are more people buried in the cemetery than are known about. Many of the early burials would have been laid to rest under simple wood crosses and these simply wouldn’t have survived the harshness of Port Fairy’s coastal weather. Despite this, the surviving burials provide a fascinating record of the life and death of the early inhabitants of the district.

There are more people buried in the cemetery than are known about. Many of the early burials would have been laid to rest under simple wood crosses and these simply wouldn’t have survived the harshness of Port Fairy’s coastal weather. Despite this, the surviving burials provide a fascinating record of the life and death of the early inhabitants of the district.

Just out of Dunkeld

Just out of Dunkeld

Grampians from a distance

Grampians from a distance

Half way up one of The Grampians

Half way up one of The Grampians

A very dry Lake Linlithgow

A very dry Lake Linlithgow The side of Mount Rouse

The side of Mount Rouse Mount Rouse from the road

Mount Rouse from the road Mount Sturgeon and Mount Abrupt

Mount Sturgeon and Mount Abrupt

The Glenelg in mid western Victoria near Harrow.

The Glenelg in mid western Victoria near Harrow.

The Glenelg much further down stream near Nelson on the Sth Australian border

The Glenelg much further down stream near Nelson on the Sth Australian border Monument just out of Dunkeld

Monument just out of Dunkeld Monument just out of Harrow

Monument just out of Harrow Balmoral

Balmoral Harrow

Harrow Avoca

Avoca Rail bridge over the Wannon in Cavendish

Rail bridge over the Wannon in Cavendish