This is a slight departure for Historical Ragbag, as I’ll be looking at a mythical figure. But it still involves research and a good story so I decided it still fit.

In researching for my novel, it’s contemporary and with merpeople but based on Welsh history and mythology, I came across a figure who gets one tantalising mention in the Mabinogion. Dylan of the Wave. The Mabinogion is a series of Welsh stories that are the foundation of much Welsh mythology. I won’t go into great detail about them here, because that is a post in and of itself, but they’re well worth a read if you get the chance. In many ways they’re even more off the wall than Greek mythology, and you can see how much some of them have seeped through into Western concepts of folklore and fairytales. You can read a free version at Project Gutenberg here but I read was the Oxford edition. You can see it in the references at the end.

Anyway, who is Dylan and why did he catch my attention?

To answer that we need to look at the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion.

The Fourth Branch is broadly the story of Math son of Mathonwy. Math is the Lord of all Gwynedd (Northern Wales today). I’ll provide a brief summary of the story as a background. There will be bits that seem like leaps in logic and that’s because they are. You have to remember that this is a medieval text and the medieval mindset can seem impenetrable to us. This isn’t an overhang of a lost pre-christian mythology, the Mabinogion is very much a Christian text and of its time.

The story kicks off with Math’s nephew Gilfaethwy in love with Math’s foot-maiden Goewin who Math won’t part with. Gilfaethwy is concerned because Math can hear everything that’s said. Math’s other nephew Gwydion (who is a magician) suggests starting a war with Powys and Deheubarth (both kingdoms in Southern Wales) so Gilfaethwy can have Goewin. There’s magical pigs involved, but a war is started and while Math is away Gilfaethwy rapes Goewin in Math’s bed.

When Math returns he discovers the rape because he can only place his feet in the lap of a virgin and Goewin is no longer one. She tells Math of Gilfaethwy’s actions. Math changes Gilfaethwy and Gwydion into a hind and a stag and binds them to mate with each other and take on the nature of the two animals for a year. At the end of the year the hind and stag return with a fawn, Math changes them into a boar and a sow and sends them out again (though he fosters the boy who had been a fawn). At the end of another year the sow and the boar are back with a young one. Math then changes them into a wolf and a she-wolf and sends them out again. Again he fosters the boy who had been the piglet. At the end of that year the wolf and she-wolf return with a cub. Math considers his nephews punished enough and restores them to men, telling them of their fine sons.

Math then asks his nephews about finding another virgin to be his foot-maiden and they suggest their sister Arianrhod. Math uses his magic to test Arianrhod’s virginity and as she steps over Math’s magic wand a large sturdy yellow haired boy drops from her, Arianrhod gives a cry and runs away but as she does something small falls from her and Gwydion gathers it in brocade and hides it in a small chest at the foot of his bed. Math take the yellow haired boy and says “I will have this one baptised. I will call him Dylan.” And he is baptised.

The Mabinogion goes on to say

As soon as he was baptised he made for the sea. And there and then, as soon as he came to the sea, he took on the sea’s nature and swam as well as the best fish in the sea. Because of this he was known as Dylan Eil Ton- no wave ever broke beneath him. The blow which killed him was struck by Gofannon, his uncle and it was one of the Three Unfortunate Blows.

This is the introduction of Dylan of the Wave.

The Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion continues with the scrap in the chest – who turns out to be a child who came to be called (after some trickery) Lleu Llaw Gyffes and Gwydion who helps him overcome various obstacles including making a wife for him out of flowers- Blodeuwedd (who gets a very unfair hand and who I’ll write something about later). But this is the only mention of Dylan in the whole of the Fourth Branch.

So why did this get me interested? Firstly because the book I’m working on is about mer people and the sea, so having a Welsh mythological figure tied to the sea so explicitly was very useful from a narrative perspective. Secondly, because in a panoply of the extraordinary Dylan sort of pops up and vanishes again, and some quick Googling doesn’t turn up masses. So I did some more digging. I started with the Three Unfortunate Blows.

This is a triad. Triad’s are a key to mythology. I’m still getting my head around them, but essentially they are circumstances or thematic instances that come in threes. They can be found throughout Welsh folklore and belief systems, as well as legal codes. They are also often reflected in bardic works and poetry, including the metre of some poetry. They are found in several surviving Welsh manuscripts and referenced in most Welsh mythology, often the same ones, they are cross referential. A good example are the three arrogant men of the island of Britain: Sawyl High Head, Pasgen son of Urien and Rhun son of Einiawn. So in the case of Dylan what were the Three Unfortunate Blows? I spent quite a bit of time trying to find the listing for them, but then worked out that unfortunately they are one of the lost triads. This means that all that has survived is mentions of them, rather than the triads themselves. One of these mentions is from the Book of Taliesin which refers to Dylan’s end, and tells us a bit more about Dylan himself as well as Gofannon who struck the blow. It’s called the Elegy of Dylan, Son of the Sea:

“One highest God, wisest of sages, greatest in might –

Who was it held the metal, who forged its hot blows?

And before him, who held still the force of the tongs?

The horsemaster stares – he has done lethal hurt, a deed of

outrage,

Striking down Dylan on the fatal strand, violence on the

shore’s waters,

The wave from Ireland, the wave from Manaw, the wave from the North,

And fourth, the wave of Britain of the shining armies.

I plead with God, God and Father of the Kingdom that knows no refusal,

The maker of Heaven, who will welcome us in his mercy.

The details about Gofannnon that the Elegy is alluding to are that Gofannon was a smith endowed with supernatural powers. Again another character embedded in a the broader mythological landscape.

This isn’t Dylan’s only mention in the The Book of Taliesin. He’s also referenced in the legendary dramatic poem The Battle of the Trees. Which is worth reading in its own right as it (at face value) tells the story of Gwydion animating the trees of a forest to fight for him. It also covers Taliesin’s creation, and this is where the line about Dylan appears. The line is a short one “I was in the citadel with Dylan, Son of the Sea.”

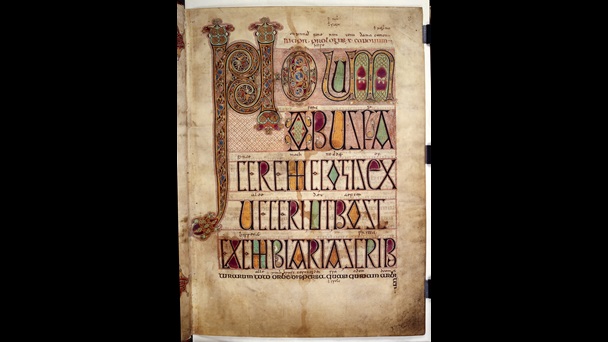

The Book of Taliesin is itself an astounding survival. It’s a manuscript dating from the first half of the fourteenth century and is a collection of poems and similar works supposedly by or about the great bard Taliesin. It’s arguable if Taliesin was a real person or not but he is the greatest of the Welsh bards, and could be a conflation of a real person from the 6th century with a mythological figure.

But, to not sidetrack myself (or not too much anyway). The Elegy presents Dylan as someone worth having an elegy written about. It and the line in The Battle of the Trees also situates him as an important being in Welsh mythology and belief, someone who appears in more than one text and someone who was well enough known to be understood from just one line.

Dylan also appears briefly in the Black Book of Camarthan too (another amazing medieval survival) where his grave is mentioned as “Where the wave makes a noise, the grave of Dylan is at Llanfeuno.” This is probably a peninsula in South Wales.

These are not the only mentions of Dylan in Welsh texts, but they give the context.

What all this means, is that there were more stories about Dylan and his exploits but they haven’t survived. Some of this is because the written sources that have survived have largely been by chance, and partly because some were certainly oral traditions and might not have been written down. Dylan does survive in odd places though, aside from all these mentions. His name is incorporated into a couple of place names, though tangentially, and rough seas and the roar of the tide at the mouth of the river Conwy is said to be the death groan of Dylan.

You can see the Conwy estuary below

There is also a school of thought that Dylan is the remnant of a lost sea divinity, and or that he was an early iteration of a merperson. While both are certainly a possibility (and something that we’ll never know), what it means for me is that I have a fairly blank slate to work from. So Dylan has become part of my world a ‘real’ building block to layer a new story on, and I kind of like that.

References:

Books:

Book of Taliesin: Translated by Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams: 9780241381137

The Mabinogion: A new translation by Sioned Davies 9780199218783

Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The triads fo the Island of Britain edited by Rachel Bromwich

9781783163052

The Celtic Myths That Shape The Way We Think by Mark Williams 9780500252369

Dictionary of Celtic Mythology by James MacKillop

https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofcelt0000mack/mode/2up

Websites:

Mabinogion Summary https://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/history/sites/themes/society/myths_mabinogion_04.shtml#:~:text=The%20final%20and%20most%20complex,Math’s%20beautiful%20foot%2Dmaiden%20Goewin.

Mabinogion Project Gutenberg:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5160/5160-h/5160-h.htm

Welsh Classical Dictionary:

Book of Taliesin:

The photo is mine