Bear’s Castle is an enigma. There is little agreement over why it was built, or its purpose, but it truly captures the imagination.

Bear’s Castle stands on the edge of the Yan Yean Reservoir, just out of Whittlesea. It’s one of those places I’d only seen photos of, so to say I was pleased to have a chance to visit earlier this year is an understatement.

Bear’s Castle is on lands run by Melbourne Water, due to the proximity of Yan Yean Reservoir, and it has gone through many uses in its life since it was built probably in the 1840s. So let’s start at the beginning, this is going to be a post with a lot of ‘possibles’ because so much is not known.

The best place to begin is with the man who gave his name to castle, John Bear. So who was John Bear?

John Bear came from a landed family in Devon. He emigrated to Australia with his entire family, servants, livestock and a few friends (they chartered a whole ship) in 1841. They arrived in Williamstown on the 20th of October 1841. Once arrived he set up as a stock and land merchant and then purchased land from the crown, an extensive 935 acres at Yan Yean (the reservoir was not built then). He built a homestead, and planted vines (one of the earliest vineyards in Victoria) and raised cattle. However, as a stock and land agent he worked mostly in the city so, somewhat unbelievably, he commuted back to Yan Yean on the weekends, leaving his younger son to run the farm.

I’d like to pause here to acknowledge that John Bear didn’t purchase uninhabited land. The lands around Yan Yean have been the home of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people for thousands of years before colonisers like Bear arrived and claimed them. As far as I can find Bear was not involved in specific massacres, but by moving into the land and turning its use over to cattle and crops, he was dispossessing the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people. This is true of any Europeans, including my own family, who arrived in Victoria in the 19th century and began to acquire vast tracts of land.

We know Bear had a house built by 1842 because the family was held up by bushrangers that year. John Bear was away, but his wife and daughter were at the house and forced to cook the bushrangers dinner. They also apparently stole Bear’s best port. This incident leads to the first suggested reason for the construction of Bear Castle, as a refuge from bushrangers or even First Nations people (who it was feared may attack the new house and not without reason). There are a few reasons against this theory, the key of which is the distance between the house site and Bear’s Castle. It would have been a long dash through often hostile bush to reach the castle, not ideal as a quick refuge.

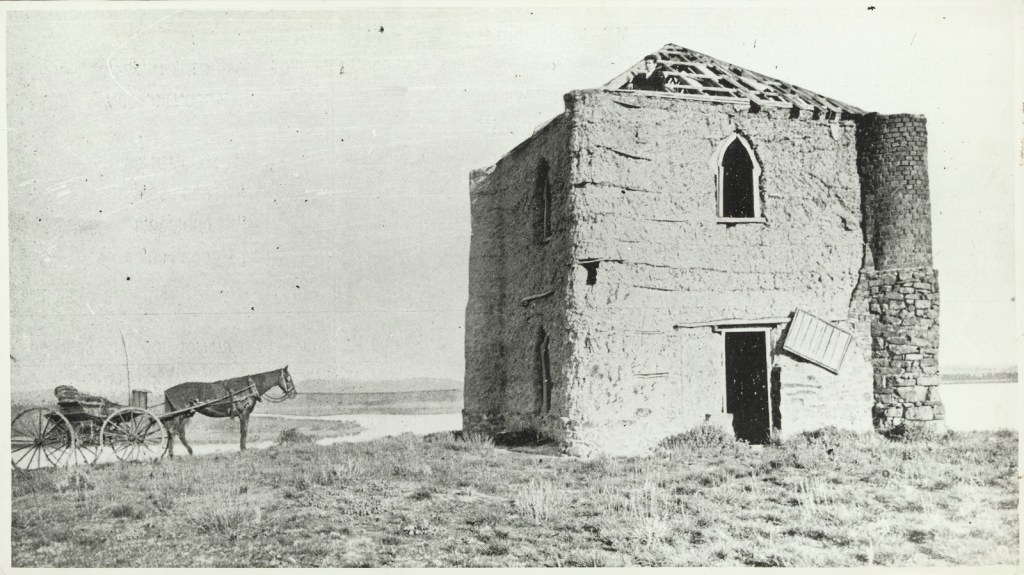

The most bandied about theory is that the castle was built due to an offhand remark by John Bear. The story is that two of his stockmen, possibly John Edwards and Thomas Hannaford- both from Devon, asked him what they should do while he was away for some months, and he flippantly replied, ‘build me a castle’. And thus they did just that. This is a story has been handed down, and is frequently accepted as the most likely reason for the construction of Bear’s Castle. It is definitely possible, as the castle is built out of cob, a traditional mud and straw building method from Devon, and it resembles follies that might have been a familiar site in Devon. You can see what it looked even more castlely in the c.1870 photo below. The people standing on the battlements are thought to be John Bear’s descendants.

Against this theory is how much time and effort the construction of Bear’s Castle would have likely taken. It seems extravagent to build on a whim. Additionally his family would have remained at the farm, it seems unlikely they would have been alright with their workmen building a castle when they could be undertaking more useful work. It could absolutely be a contributing factor though.

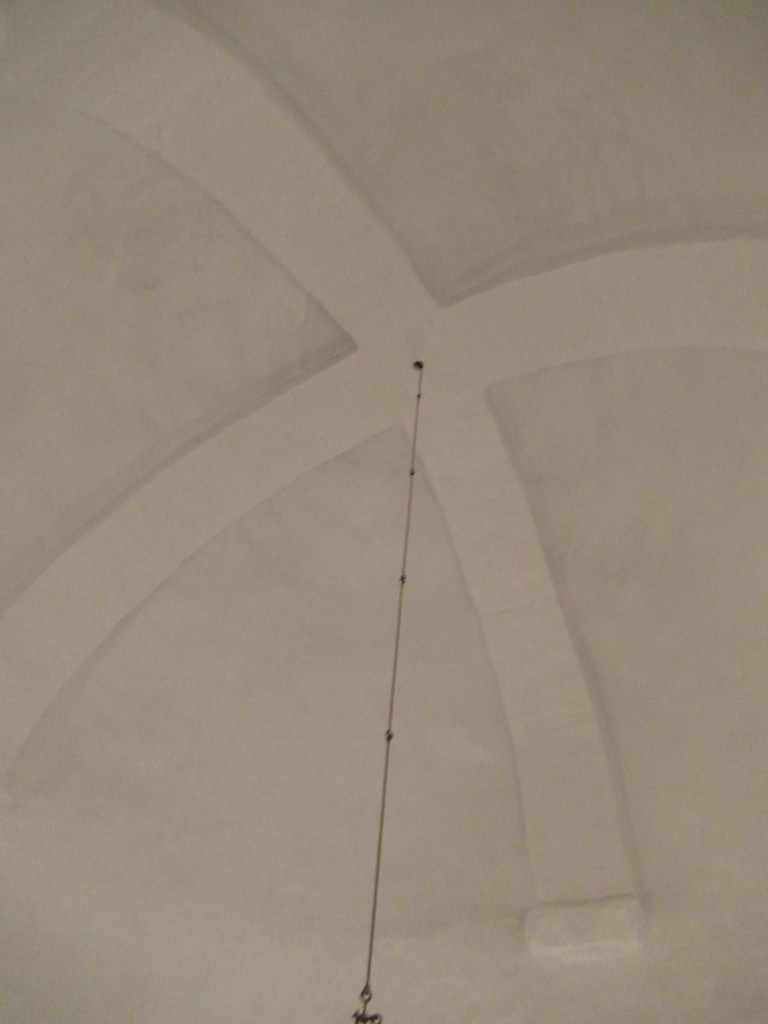

The castle was definitely finished by 1851 because the farm was renamed Castle Hill after devastating bushfires ravaged the area. These fires indicate another possible reason for the construction of the Castle, as a look out tower. This is probably the most plausible, the castle is clearly not built to be lived in long term (though the Duffy Family did occupy the castle for a short time in 1865 while a house was being built for them). But the top would have given commanding views across the landscape to watch for threats. Originally the battlements would have been reached by a ladder probably from the first floor. This first floor was probably no more than a mezzanine level that was used to access the battlements (which are no longer there) rather than a floor that was actually used as another storey. There isn’t really anything left of the floor, but there is a couple of piece of sugar gum which were most likely installed by Melbourne Water in the 1970s. They never finished installing anything more permanent.

The mezzanine was reached by stairs built into the castle wall.

So regardless of whether the castle was built as a refuge, a watch tower, a folly, or a combination there of, it was built and the history of the building itself is somewhat circumstantial but still interesting. It was probably built in the 1840s, most likely the late 1840s. It’s gone through many iterations. The walls are mainly cob, though what you see now as the exterior walls was done as a render with mud and chicken wire in the 1970s in an attempt to protect the building. You can see some of the exposed wire below.

The pitched roof that you can see now, appeared in a thatched form in the 1920s, but it was soon in extensive disrepair.

The roof was re-clad in timber shingles in the 1940s

Although the above photos are black and white, before its 1970s render the castle would have been grey from the clay it was built out of. Hidden beneath the 1970s render, as well as the original building material, are small details such as that the lancet windows were formed from inverted forks of gum trees. You mostly can no longer see the gums, but the inverted shape is distinctive.

You can see original materials peaking out from the 1970s render as well.

There is also a fireplace in Bear’s Castle

The chimney tower was built in the 1870s you can see how different it is from the other towers below

It’s the only extensive use of the bricks in the building.

Bear’s Castle’s survival is at least partly because it sits next to Yan Yean Reservoir which was constructed in the 1857 and is Victoria’s oldest water supply. When the reservoir was built it was the largest artificial reservoir in the world.

It was designed by James Blackburn, who was a civil engineer from England transported for embezzlement. It took four years to build, cost 750 000 pounds and has a capacity of 30 000 megalitres. Its status as a major source of water supply means that public access to Bear’s Castle has been restricted to protect the purity of the water. This probably contributed to both its survival, no chance to loot materials, and it’s obscurity; as even today you have to go on an organised, weather dependant tour to visit it.

Bear’s Castle is a unique survival, it’s the only cob building left in Victoria and is one of the state’s oldest. It stands for what were probably many cob buildings in the Yan Yean and Whittlesea area which have not survived. Whatever its purpose, it tells a story of an early pastoralist family bringing their history and traditions with them. Its very castle like nature tells of the hundreds of years of Eurpoean history imposed on the land. And if nothing else it is a mesmerising building.

References:

Site Visit 2023

Bear’s castle Conservation Plan June 1997

https://www.whittleseainfocentre.net.au/BearsCastle

https://www.parks.vic.gov.au/places-to-see/parks/yan-yean-reservoir-park

Images:

All modern photos are mine.

c.1872 image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bear%27s_Lookout_Castle_Hill_Yan_Yean_c1870.jpg

Early 1900s image:

https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/1sev8ar/alma9920982713607636

1940s image:

https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/1sev8ar/alma9917309423607636

John Bear image:

https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/1sev8ar/alma9918066113607636

The three cannons inside the upstairs room remain because it is impossible remove them.

The three cannons inside the upstairs room remain because it is impossible remove them.

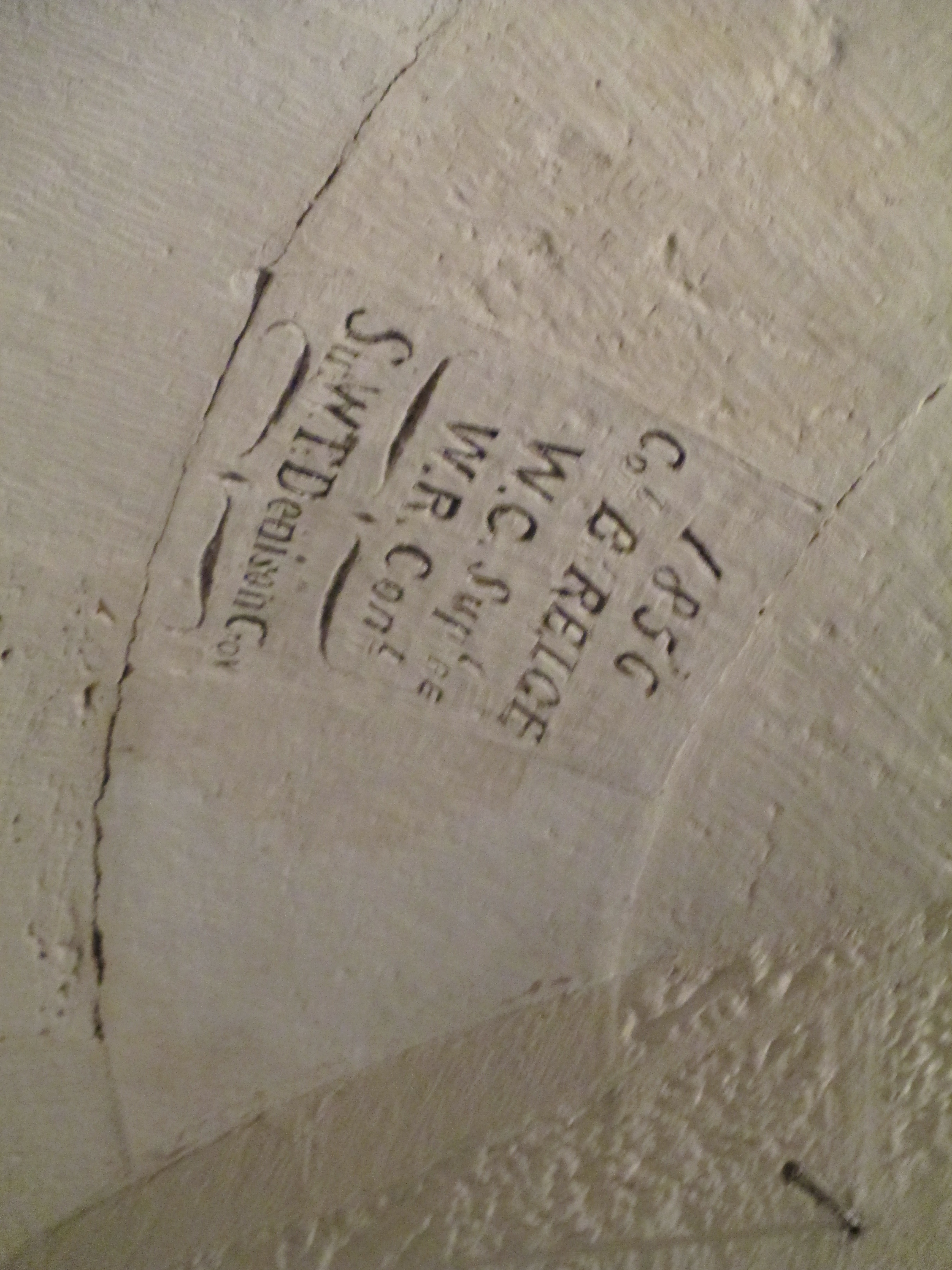

They were winched into place and then the roof was finished over them. As you can see from the keystone it was completed in 1857.

They were winched into place and then the roof was finished over them. As you can see from the keystone it was completed in 1857.

.

.

It is, however, its completeness as a 12th century wooden structure inside and out, and especially the carvings, which make it truly remarkable.

It is, however, its completeness as a 12th century wooden structure inside and out, and especially the carvings, which make it truly remarkable. There were once over 1000 stave churches in Norway, but now only 28 remain. Most were built between 1130 and 1350 though a few are later. The black death affected the construction of new buildings after the mid 14th century. The reason they survived, even though they are wooden, is because the wood is coated regularly in pitch to protect it from the weather (this is still done at Urnes). In the case of Urnes it has a stone foundation, which stops it rotting from the ground up. The previous church on the site was a post hole church, the holes have been found in archaeological investigations.

There were once over 1000 stave churches in Norway, but now only 28 remain. Most were built between 1130 and 1350 though a few are later. The black death affected the construction of new buildings after the mid 14th century. The reason they survived, even though they are wooden, is because the wood is coated regularly in pitch to protect it from the weather (this is still done at Urnes). In the case of Urnes it has a stone foundation, which stops it rotting from the ground up. The previous church on the site was a post hole church, the holes have been found in archaeological investigations.

The carving above is the side door which is no longer used, but would most likely have originally been the main entrance. You can see a stylised lion in the carvings on the left. These carvings most likely come from the exterior of the earlier church and were reused in the current church. You can see the interior of the door below.

The carving above is the side door which is no longer used, but would most likely have originally been the main entrance. You can see a stylised lion in the carvings on the left. These carvings most likely come from the exterior of the earlier church and were reused in the current church. You can see the interior of the door below.

Leaving aside the exterior of the church for the moment, the interior is just as if not more impressive.

Leaving aside the exterior of the church for the moment, the interior is just as if not more impressive.

Along with a medieval bishop’s chair

Along with a medieval bishop’s chair

and the chandelier which hangs from the ceiling

and the chandelier which hangs from the ceiling The gallery you can see part of above the chandelier, and above the chancel in the earlier photo, was added later and sadly involved cutting some of the original columns and capitals.

The gallery you can see part of above the chandelier, and above the chancel in the earlier photo, was added later and sadly involved cutting some of the original columns and capitals.

The paintings and figures you can see on the walls are also 17th century.

The paintings and figures you can see on the walls are also 17th century.

And the gargoyles.

And the gargoyles. All buildings should have at least one gargoyle.

All buildings should have at least one gargoyle.

The columns and brackets are cast iron which were made in a foundry in Carlton. They were covered with canvas, fixed with white lead and cement and had five coats of oil paint. The ceiling was hand painted and gilded. In the centre of each panel are the shields and arms of England, Scotland and Australia as well as the arms of the bank and the arms of the main cities in which it operated.

The columns and brackets are cast iron which were made in a foundry in Carlton. They were covered with canvas, fixed with white lead and cement and had five coats of oil paint. The ceiling was hand painted and gilded. In the centre of each panel are the shields and arms of England, Scotland and Australia as well as the arms of the bank and the arms of the main cities in which it operated. The details on the walls are truly impressive

The details on the walls are truly impressive The beautiful tiled floor is not original but it was based on the original colours and patterns.

The beautiful tiled floor is not original but it was based on the original colours and patterns. There is also a magnificent stained glass window. Up the very top you can see a miner ‘panning off’ which is meant to represent the origins of the wealth of Victoria. The central figure is a woman representing ‘labour’. The window also depicts the coats of arms of both Britain and Australia and symbols of the four divisions of the globe.

There is also a magnificent stained glass window. Up the very top you can see a miner ‘panning off’ which is meant to represent the origins of the wealth of Victoria. The central figure is a woman representing ‘labour’. The window also depicts the coats of arms of both Britain and Australia and symbols of the four divisions of the globe.

Barrenjoey was not the first light station in this position. The first light station was only oil lamps on two wooden towers and stood between 1865 and 1881. The current structure was built by Isaac Banks with a team of Scottish labourers and designed by government architect James Barnet. Barnet was responsible for many buildings in Sydney and he deliberately designed the slightly curved rail around the top of the lighthouse for aesthetic reasons. The rails are original, and they produce quite a vertiginous effect when standing next to them.

Barrenjoey was not the first light station in this position. The first light station was only oil lamps on two wooden towers and stood between 1865 and 1881. The current structure was built by Isaac Banks with a team of Scottish labourers and designed by government architect James Barnet. Barnet was responsible for many buildings in Sydney and he deliberately designed the slightly curved rail around the top of the lighthouse for aesthetic reasons. The rails are original, and they produce quite a vertiginous effect when standing next to them.

A lighthouse needs to be identifiable from sea and today Barrenjoey operates 4 flashes separated by a 2 second interval every 30 seconds.

A lighthouse needs to be identifiable from sea and today Barrenjoey operates 4 flashes separated by a 2 second interval every 30 seconds. George Mulhall was born in c.1811 in Australia and both his parents were convicts from Ireland. George was appointed lighthouse keeper in 1868 and his son who was George Jr became assistant keeper. This was before the construction of the current lighthouse and the keepers lived off the Peninsula on what is now the third tee of the Palm Beach Golf Course. When the lighthouse began operating in 1881 George was the principal lighthouse keeper. There were stories that George died from being struck by a bolt of lightning and burnt to cinders, but his dead certificate describes him as having died from a stroke in 1885. His wife Mary who died in 1886 is buried with George. It is a truly beautiful spot to be buried.

George Mulhall was born in c.1811 in Australia and both his parents were convicts from Ireland. George was appointed lighthouse keeper in 1868 and his son who was George Jr became assistant keeper. This was before the construction of the current lighthouse and the keepers lived off the Peninsula on what is now the third tee of the Palm Beach Golf Course. When the lighthouse began operating in 1881 George was the principal lighthouse keeper. There were stories that George died from being struck by a bolt of lightning and burnt to cinders, but his dead certificate describes him as having died from a stroke in 1885. His wife Mary who died in 1886 is buried with George. It is a truly beautiful spot to be buried.

The stain glass window dedicated to St Thomas also carried a dedication for the A’Beckett family on its base

The stain glass window dedicated to St Thomas also carried a dedication for the A’Beckett family on its base The A’Becketts were a prominent district family and the font is also dedicated to one of their number.

The A’Becketts were a prominent district family and the font is also dedicated to one of their number.

Port Fairy’s Griffiths Island is now connected to the mainland by a causeway,

Port Fairy’s Griffiths Island is now connected to the mainland by a causeway,  But in the 1800s the island was only accessible by boat and it was often dangerously rough so was cut off completely from the mainland. It was extremely isolated. The island was originally 3 islands, Rabbit (on which the light house stands), Goat and Griffiths. They have joined together as one island, partly from coastal erosion and partly from the construction that surround the islands. They serve to protect the entrance to Port Fairy. Rabbit island would have been extremely remote in the 1800s.

But in the 1800s the island was only accessible by boat and it was often dangerously rough so was cut off completely from the mainland. It was extremely isolated. The island was originally 3 islands, Rabbit (on which the light house stands), Goat and Griffiths. They have joined together as one island, partly from coastal erosion and partly from the construction that surround the islands. They serve to protect the entrance to Port Fairy. Rabbit island would have been extremely remote in the 1800s.