Welcome to this guest post by Sam Mee, the founder of the Antique Ring Boutique.

Walk through Australian cities today and you can’t miss their 19th-century Victorian inheritance. St Paul’s Cathedral towers above Melbourne’s commercial skyline while Flinders Street Station still dictates the city’s transport logic, much as the original terminus did 150 years ago. Sydney’s sandstone buildings, like the General Post Office, continue to project institutional power even among more modern buildings.

The permanence isn’t just a historical quirk. These buildings were designed not just to endure but to control and instruct – to assert order, authority and moral certainty in a society that Britain worried might otherwise unravel. Victorian Britain did not aim just to colonise Australia. It wanted to transplant moral and cultural discipline.

Of course, this project did not unfold on empty land. Victorian ideals were imposed on landscapes that already been shaped by Indigenous law, culture and knowledge system. And the way they were enforced was inseparable from dispossession and violence. Churches, railways, schools and civic institutions became instruments of exclusion as well as of order.

Exporting Victorianism

Victorian ideals arrived in Australia as more than vague notions of Britishness. They formed a coherent ideology grounded in Protestant morality, faith in progress, social hierarchy and the conviction that civilisation could be built. Victorian administrators thought firm guidance was needed to keep stable a distant colony populated by convicts and Indigenous peoples.

Henry Parkes, often called the “Father of Federation”, shows how Victorian ideals hardened into Australian institutions. He rose from poverty through self-education, exemplifying the Victorian belief in self-help. As Premier of New South Wales, he promoted social improvement through free, compulsory education, through public works and through welfare reforms. These reflected the conviction that a civilised society could be built through institutions. He combined liberal reform with strong imperial loyalty. He championed representative government and also tried to end convict transportation while remaining devoted to Britain, famously describing a “crimson thread of kinship” linking the colonies and the Crown. His 1889 Tenterfield Oration (https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/tenterfield-oration) framed Australian federation as both a moral and national destiny.

Moral regulation in a new land

British Victorian society had strict moral codes and Australian colonial authorities quickly tried to impose these same standards of sexual propriety, sobriety and religious observance.

Licensing laws such as Victoria’s Licensing Act of 1852 and New South Wales’s Sale of Liquors Licensing Act of 1862 (NSW) regulated pubs in gold-rush towns, restricted opening hours and gave the police broad powers of inspection. Police courts in centres like Ballarat routinely prosecuted public drunkenness, treating excessive drinking as a moral/civic offence. Temperance organisations such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union gained influence in the late 19th century, alongside Sunday trading restrictions and Sabbath laws that enforced Protestant ideals of work and rest. Marriage and family life were seen as defences against disorder with women cast as moral guardians of the home. These views persisted – in Victoria, for instance, public drunkenness was only formally decriminalised in 2021. And retail hours are still restricted on Sundays in several states. You can listen to the history of Australia’s licensing laws here: https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/latenightlive/history-alcohol-law-australia/101969150.

Some colonies copied British Contagious Diseases Acts (CDAs) between the 1860s and 1880s, mirroring (and in some cases outlasting) UK laws designed to combat sexually transmitted disease. The laws allowed police to forcibly examine and detain women suspected of prostitution in “lock hospitals” for treatment, leading to severe restrictions on their liberties. These measures directly replicated British practice, where working-class women in towns and ports were subjected to compulsory medical examination. Obviously the view was that female sexuality, not male behaviour, posed the greatest social risk. Overall, the idea of respectability divided “deserving” settlers from unruly miners, the urban poor and racially marginalised groups. In practice, this meant that poor and working-class women could be detained without trial on the basis of suspicion alone, while male clients faced no equivalent scrutiny.

Gothic architecture and the moral landscape

Few legacies of Victorian influence are as obvious as Gothic Revival architecture (see examples here: https://www.thearcagency.com.au/resources/echoes-of-gothic-the-lasting-influence-of-church-architecture-on-modern-design

This look came to dominate Australian cities – and still does in its historic centres – because it offered a powerful visual language for imperial identity. It was closely associated with Britain and Christian tradition and favoured by both Anglican and Catholic institutions, particularly under the influence of Augustus Welby Pugin. His designs allowed medieval forms to be convincingly reproduced using local materials such as Sydney sandstone and Melbourne basalt. Stained glass and ornate stonework were used not only on churches but also on public buildings and railway stations to give a deliberately European feel. Funded by gold-rush wealth, Gothic Revivalism gave new Australian cities a sense of cultural depth. Indeed, Pugin’s writings argued that Gothic architecture was inherently moral and superior to classical styles associated with paganism or republicanism. Gothic forms also appeared in secular institutions such as the University of Melbourne, where medieval architectural language lent new colonial education the authority and gravitas of ancient European learning.

Controlling gold rush towns

The mid-19th century gold rushes posed the biggest challenge to Victorian ways of thinking in Australia. From the early 1850s finds in New South Wales and Victoria, gold discoveries drew in hundreds of thousands of migrants from Britain, Europe, China and North America. Rapidly expanding settlements of tents and diggings emerged near goldfields almost overnight, forming makeshift towns outside of existing established law and infrastructure. These boomtown societies were dominated by single men of many races who gambled and drank alcohol – all things that Victorians associated with moral disorder. (Watch a live sketch history of the gold rush here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iU9iV56F86s

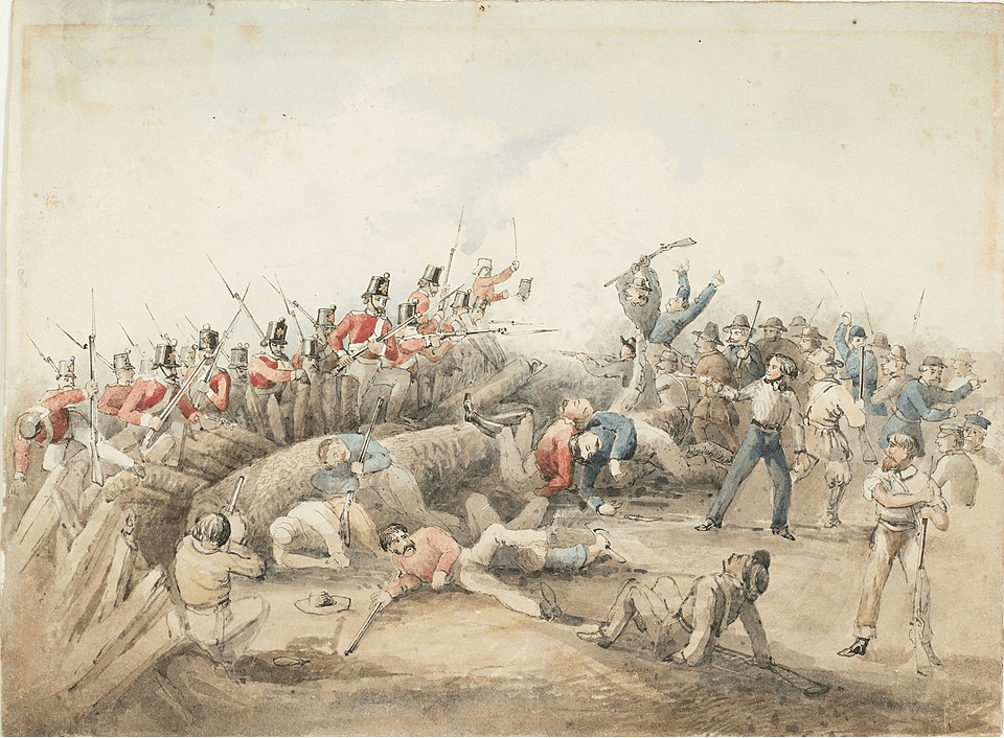

At first, the colonial authorities tried to impose control using a mining licence system, which required diggers to pay fees and submit to police inspections. Resentment at this system led to the 1854 Eureka Stockade, an armed uprising by miners at Ballarat against what arbitrary taxation and heavy-handed policing (https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/eureka-stockade).

Although this rebellion was quickly put down, it did force the colonial governments to reconsider how to control the goldfields. And so after Eureka, reforms in 1855 replaced the punitive licence system with the Miner’s Right, regulating who could mine while linking access to political rights. Colonial police forces were expanded to enforce order and were complemented by town planning schemes that rapidly replaced tents with surveyed streets and permanent buildings.

What’s crucial, though, is that these measures were not simply about managing gold extraction but were designed to transform rough and ready mining camps into disciplined communities. Colonial governors such as Sir Charles Hotham, who governed Victoria from 1854 to 1855, saw the goldfields as moral battlegrounds. His policies reflected a broader Victorian belief that order and institutions could convert chaotic frontier settlements into respectable towns aligned with imperial ideals of civilisation.

Infrastructure as moral progress

Victorian faith in progress was enthusiastically expressed in infrastructure. Railways, roads, bridges, telegraph lines and sanitation systems were celebrated not only as practical achievements but as a sign that civilisation was taking root. Projects such as the expansion of the Victorian rail network from Melbourne into the goldfields and the introduction of sewerage systems in cities were framed as evidence of discipline. These projects were celebrated as civilising achievements, ignoring their effect on land already structured by Indigenous knowledge systems.

Railways in particular embodied Victorian ideology – both in Australia and back in the UK. Contemporary figures such as Alfred Deakin, writing in the 1880s and 90s, described railways and water schemes as the way that Australia could be “made” into a modern nation rather than a scattered frontier.

Timetabled rail services also standardised time across the colonies and tied distant towns into a coherent administrative and economic system. Rail tracks shot out from colonial capitals to ports and mining centres. They promised equality of access but enabled state surveillance and government control over movement.

Less acknowledged was the cost: colonial infrastructure routinely cut across Indigenous landscapes and songlines with rail corridors, and property boundaries that reflected British priorities rather than local ones. Victorian progress was never neutral. It imposed a single vision of order at the expense of others, a legacy that remains embedded in Australia’s built environment and public debate: “Aboriginal people’s entanglements with the New South Wales railways have involved dispossession, removal, employment, mobility, and travel, including the forced removal of children known as the Stolen Generations.” (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1745-5871.12675)

Long-term effects

Modern Australia likes to imagine itself as egalitarian and forward-looking but much of its social and physical landscape was shaped by the Victorian worldview. And a similar gap between ideal and reality existed in the 1800s. Alcohol consumption remained high. Violence persisted. The promise of moral uplift frequently clashed with economic exploitation and racial hierarchy.

These contradictions remain visible today. Australia continues to wrestle with the legacy of Victorian moral frameworks imposed on Indigenous communities, particularly through education, land use, legal systems and violence (https://www.workingwithindigenousaustralians.info/content/History_3_Colonisation.html).

Victorianism didn’t just build colonial Australia; it sought to discipline it. And the structures through which that discipline operated still shape Australian life today.

About the author

Sam Mee is the founder of the Antique Ring Boutique (https://www.antiqueringboutique.com/en-au), and sells rings from the Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian and Art Deco eras. You can read more about Victorian jewellery here: https://www.antiqueringboutique.com/en-au/pages/victorian

A note from Ellen

I just wanted to thank Sam for the post, and to acknowledge in the tradition of Historical Ragbag that many of the advantages for the colonisers that Sam discusses in the post are structures that I have directly benefitted from with both sides of my family arriving in the 1850s as these structures were being actively imposed.

Very interesting, as always.

LikeLike

thanks Lyn, it’s been interesting having a guest writer

LikeLike