Østerlars Church is on Bornholm, an island I have already discussed in a previous post on Hammerhus Castle which you can read here. Østerlars is truly remarkable. It is only one of four round churches on Bornholm, but it’s the biggest and the oldest.

Østerlars was constructed c. 1150 and is dedicated to Saint Lawrence. The name comes from a contraction of Laurentii Kirke which became Larsker and eventually Østerlars (øster meaning east) to distinguish it from another nearby church dedicated to St Nicholas.

As you can see Østerlars is round, apart from the little belfry built off to the side (which holds two bells dating from the 1640s and the 1680). As to why it was built round? There are a number of opinions, but no one knows for certain. It is possible that Østerlars and the other round churches on Bornholm were either inspired by or built by the Knights Templar. The Templars certainly built round churches (you can see two below from London and Cambridge), they were modelled on the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. There is also a connection between Eskil the Archbishop of Lund and Bernard of Clairvaux who played a role in the foundation of the Knights Templar, so it isn’t impossible.

Another, possibly more likely, answer is that the churches were built as fortifications, and the round shape was part of making the church more impenetrable. Østerlars was certainly built with many features that made it work as a fortification, originally the church wouldn’t have had a roof, and would have had a lower outer wall so it was possible to move around the outer passage that is now under the roof.

The walls are more than 2 m thick and the church sits on a site that commands a view of the country side.

There are also holes for a large bar on either-side of the main door, which argues that the church was probably built to ward off attack. If Østerlars was a fortification, it was probably never attacked as there’s no archaeological evidence of any battles on the site. It was most likely intended to be a place of protection and retreat for the congregation as well as a place of worship. Bornholm is in an important spot on the trade routes in the Baltic and was subject to attack by pirates as well as being a place of contention between several countries. The other possible theory is that Østerlars was built partly as an observatory. It’s also not impossible that Østerlars is circular for a combination of all three reasons.

Regardless of why Østerlars is round, it is beautiful. The conical roof isn’t original, the current version dates to 1744 and every single tile is wooden, but there are drawings from the late 17th century that show a very similar roof. The shingles on the roof are made from split Bornholm oak, they are regularly tarred to keep the weather out and are remarkably durable. These days modern equipment is used when the tiles need to be re-tarred, but in the past a chair was hung from the roof to administer the tar. You can see both the interior of the roof and the chair in the photos below.

It is also an extremely solid building, with 2m thick walls built in the double wall structure, with a cavity filled with soil and gravel. All the material was sourced locally. The walls are thick enough to have a stair running up to the second floor, as well as a substantial passage around the top of the church.

The interior of the church itself is no less impressive with an altar with the original stones. An organ, the font and the curved pews were added in later with successive renovations.

By far the most impressive part of the interior of Østerlars is the frescos. They were originally painted in the early 14th century, covered with limewash around 1600 as part of the Reformation and not rediscovered until 1889. They circle around the nave’s load bearing pillar and tell the story of the life of Jesus, beginning with the annunciation to Mary and ending with a very impressive depiction of judgement day.

You can see the story narrative unfold in the photos below.

As you can see, not all of the frescoes have survived. Also, there would originally have been more in other parts of the church. For contemporaries they would have been illustrative of the priest’s sermon which would have been in latin which was unlikely to have been understood by the locals. They are a truly incredible insight into the medieval world, in their depiction of clothing and garments and dreams and fears. Frescos from this era are not common, and these are a remarkable survival.

The landscape Østerlars stands in is an ancient one as well, with Iron Age, Roman and Viking settlements and artefacts. The Viking artefacts are particularly prominent with more than 40 runestones found on Bornholm. Three such stones were built into the fabric of Østerlars. The one you can see in the photo below was built into the belfrey before being removed. It reads: Broder and Edmund had this stone raised in memory of their father Sigmund. Christ and Saint Mikkel and Saint Mary help his soul. It dates to the mid to late 11th century.

Østerlars is still an active church, as well as being a building of national importance. It is very much central to its landscape and the history of Bornholm as well as being a truly beautiful and unique building.

References

Site visit 2018

Østerlars Church Booklet.

All the photos are mine.

It is, however, its completeness as a 12th century wooden structure inside and out, and especially the carvings, which make it truly remarkable.

It is, however, its completeness as a 12th century wooden structure inside and out, and especially the carvings, which make it truly remarkable. There were once over 1000 stave churches in Norway, but now only 28 remain. Most were built between 1130 and 1350 though a few are later. The black death affected the construction of new buildings after the mid 14th century. The reason they survived, even though they are wooden, is because the wood is coated regularly in pitch to protect it from the weather (this is still done at Urnes). In the case of Urnes it has a stone foundation, which stops it rotting from the ground up. The previous church on the site was a post hole church, the holes have been found in archaeological investigations.

There were once over 1000 stave churches in Norway, but now only 28 remain. Most were built between 1130 and 1350 though a few are later. The black death affected the construction of new buildings after the mid 14th century. The reason they survived, even though they are wooden, is because the wood is coated regularly in pitch to protect it from the weather (this is still done at Urnes). In the case of Urnes it has a stone foundation, which stops it rotting from the ground up. The previous church on the site was a post hole church, the holes have been found in archaeological investigations.

The carving above is the side door which is no longer used, but would most likely have originally been the main entrance. You can see a stylised lion in the carvings on the left. These carvings most likely come from the exterior of the earlier church and were reused in the current church. You can see the interior of the door below.

The carving above is the side door which is no longer used, but would most likely have originally been the main entrance. You can see a stylised lion in the carvings on the left. These carvings most likely come from the exterior of the earlier church and were reused in the current church. You can see the interior of the door below.

Leaving aside the exterior of the church for the moment, the interior is just as if not more impressive.

Leaving aside the exterior of the church for the moment, the interior is just as if not more impressive.

Along with a medieval bishop’s chair

Along with a medieval bishop’s chair

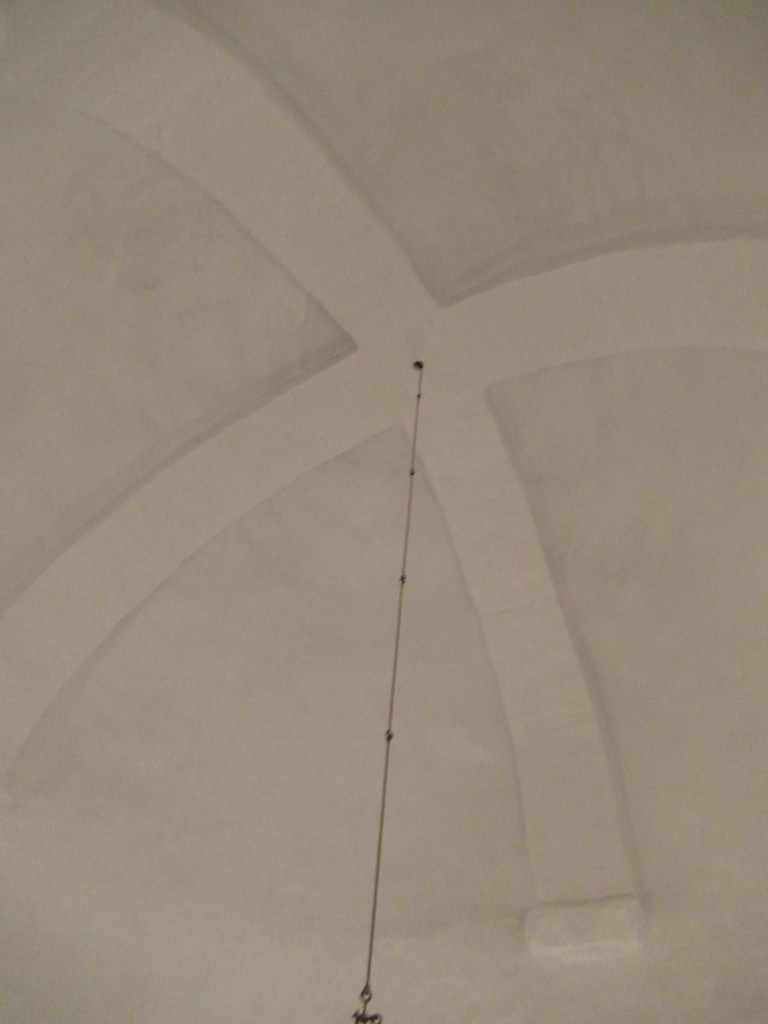

and the chandelier which hangs from the ceiling

and the chandelier which hangs from the ceiling The gallery you can see part of above the chandelier, and above the chancel in the earlier photo, was added later and sadly involved cutting some of the original columns and capitals.

The gallery you can see part of above the chandelier, and above the chancel in the earlier photo, was added later and sadly involved cutting some of the original columns and capitals.

The paintings and figures you can see on the walls are also 17th century.

The paintings and figures you can see on the walls are also 17th century.