Mechanics’ Institutes are something that most people will be vaguely familiar with. They’ll have some idea of halls in country towns, possibly something to do with cars? But the concept of Mechanics’ Institutes is much more than this. This post is not intended to be an exhaustive history of Mechanics’ Institutes, but rather an introduction to the concept and the ideals, a little of their origin and a brief run through some examples of Mechanics’ Institutes that still exist today in Victoria, Australia.

To begin with, the term mechanics in this case has nothing to do with cars. In the sense that it was used in the early 1800s it simply meant ‘worker’. Sort of the equivalent of blue collar workers today. The basic concept of a Mechanics’ Institute is usually a member owned and run group, set up by the community that provides self educational opportunities. These opportunities were normally through lectures, entertainments and often through the provision of a lending library. These were institutions that were run for members, providing free, or largely free, educational opportunities at a time when formal education was for the wealthy and the clergy. The lectures were usually run in the evenings to allow workers to attend. These were not government run institutions, they were started by local communities and had no centralised control, which makes their prevalence and ongoing existence even more remarkable.

The first Mechanics’ Institute was begun in Glasgow in c.1800 with Dr George Birkbeck of the Andersonian Institute in Scotland when he gave a series of lectures to local workers. The lectures proved to be very popular and the Edinburgh School of Arts was formed in 1821 and the London Mechanics’ Institute in 1823.

The movement spread quickly to Britain’s colonies and they were extremely prevalent in Australia, which is where I’m going to be focusing. The first Mechanics’ Institute in Australia formed in Hobart 1827, but it wasn’t long before they reached Victoria. It is worth pausing here to note that these institutions weren’t always known as Mechanics’ Institutes. They usually were in Victoria, but in New South Wales School of Arts is the more common name. They have many other names though, from Athenaeum through to Temperance hall, through to Agricultural Institute. They all held to the same principle of the provision of opportunities for self education.

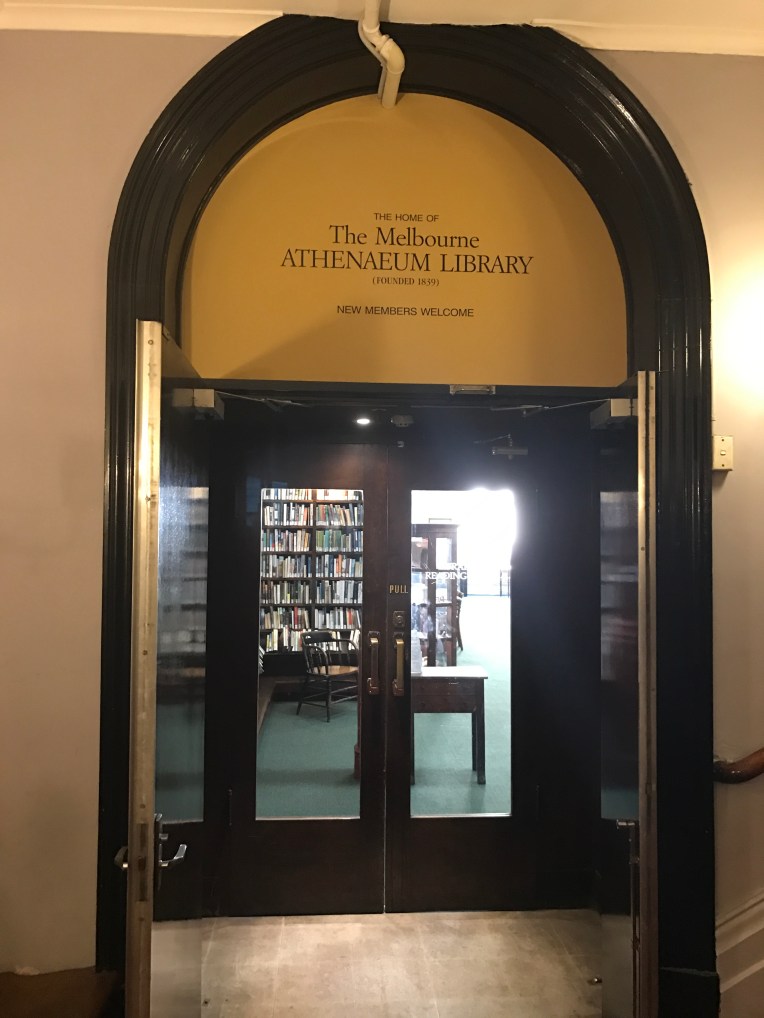

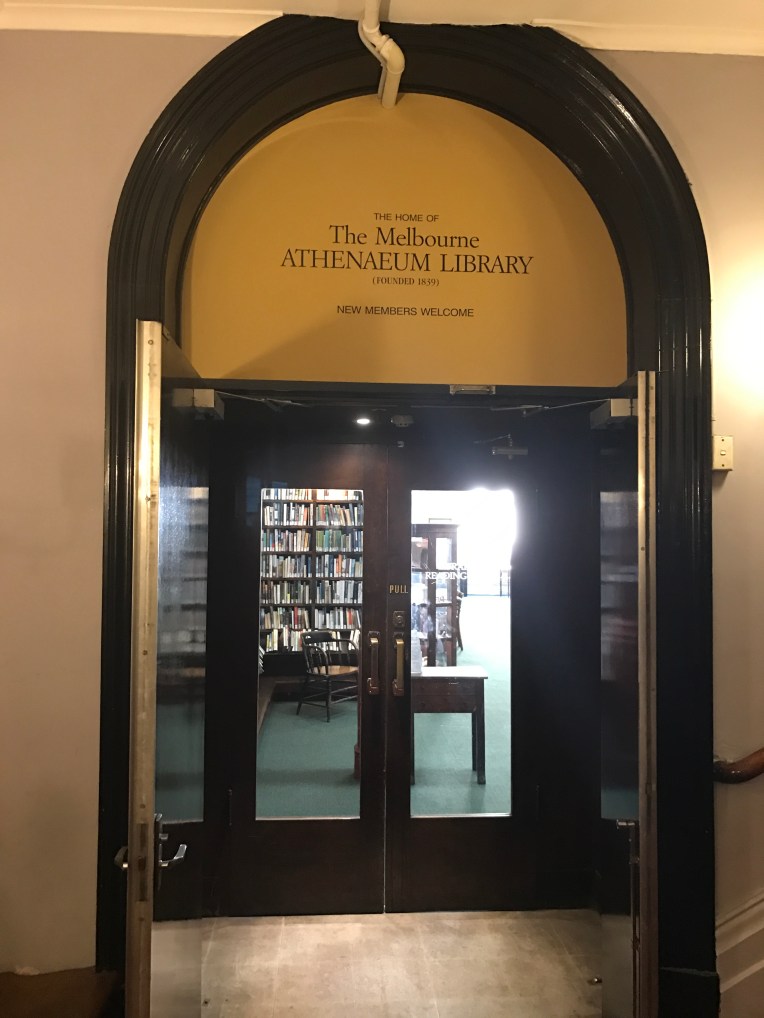

The first Mechanics’ Institute in Victoria Australia was the Melbourne Mechanics’ Institute, which was founded in 1839 and is now known as the Melbourne Athenaeum (the name was changed in 1872). Ultimately there were over 1000 Mechanics’ Institutes in Victoria at their peak, which is truly remarkable given that there was not a centralised organisation setting them up, though many did receive government funding. Most of these were in country towns and most held: a hall, a library, reading rooms, facilities for games and programs for educational activities. More than 500 remain physically, with the halls used by the local community. There are only a handful though that continue to operate as Mechanics’ Institutes. 12 are still operating from their original buildings, 10 have their original library collections, and four others exist on other sites with their collections. Roughly 6 are still operating as a lending library service. There is even one that is still incorporated with its own act of parliament.

With this number of Mechanics’ Institutes there is no way I am going to cover them all, but I have visited quite a few and I thought I’d go through and provide a few photos and a bit of history on each of them. I am using the remarkable book These Walls Speak Volumes for the majority of the history for these sites, so if you want to know more get your hands on a copy. It covers all the Mechanics’ Institutes in Victoria. The below list is alphabetical and is only based on Institutes I have been to and have photos of.

Ballan Mechanics Institute.

Ballan Mechanics’ Institute. The institute was established in 1860, though the current building dates to 1887. The ‘new’ building was erected in 1887 because the previous 1860 site was not central enough. In 1894 the Mechanics’ Institute had 1680 books. The building was fully renovated in 1922. Today the building is used as the local council library as well as being used by many community groups.

Berwick Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library.

Berwick Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library was founded in 1862, though the current building dates to the 1980s. Berwick didn’t have a substantial hall the way other Mechanics’ Institutes did, but they still hosted events. After the early 1900s the focus shifted to the library, a function it maintains to this day. In the 1980s Lady Casey provided funding for the construction of the new building which was completed in 1982 and the pre existing 500 year lease was extended. Berwick holds the private library of Lord and Lady Casey as well as some of their art and an extensive general collection. It operates as a public library. You can search their collection here.

Briagolong Mechanics’ Institute Hall.

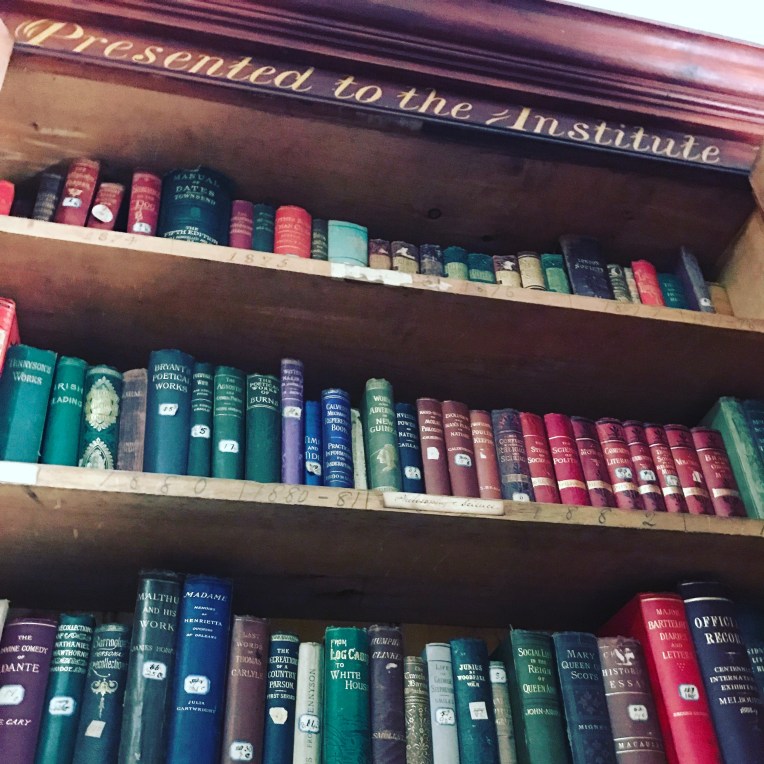

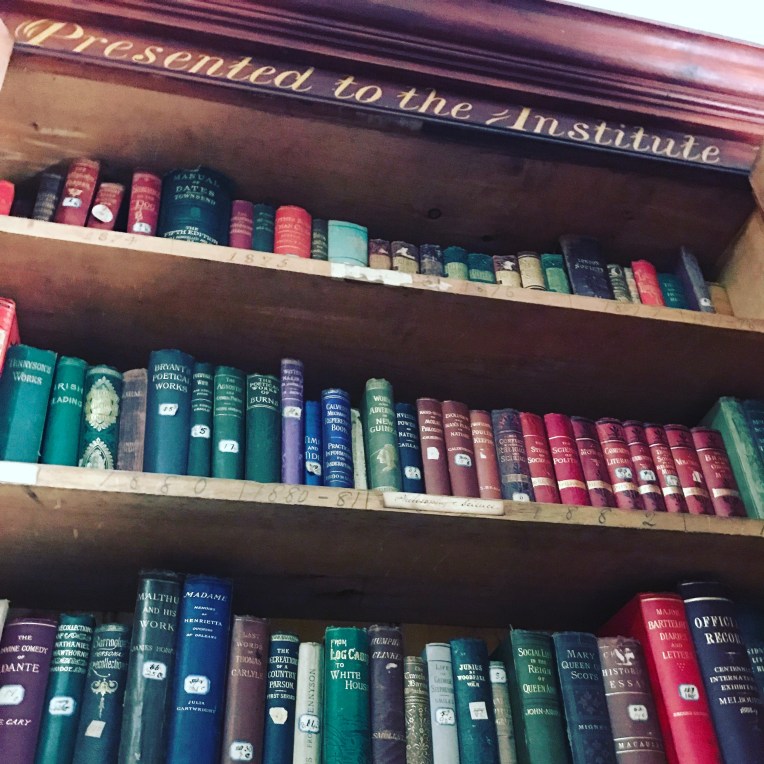

Briagolong Mechanics’ Institute Hall was established in 1874 and still stands in its original building. The hall was the first part built with the reading room and kitchen added in 1879, the third addition, including the stage, was opened in 1887. There were further additions as time went on including a 1999 addition which houses the Briagolong Community House. The library ran from 1874 for 90 years. The fact that a significant part of the original library collection survives intact is because the doors to the library were locked for some time and the books just left in there. You can see some of the remaining collection, which is housed in what was for a time the billiard room, in the photos above.

Bunyip Public Hall

The Mechanics’ Institute dates to 1905, but the current building was built in 1942. The hall was used for everything from ANZAC celebrations to rollerskating. The hall burnt down in 1940 but it was rebuilt, as you can see it today, by 1942. The new building is built in greek revival style and is under the ownership of the council. Today it is used for everything from tai chi to playgroups.

The Mechanics’ Institute dates to 1905, but the current building was built in 1942. The hall was used for everything from ANZAC celebrations to rollerskating. The hall burnt down in 1940 but it was rebuilt, as you can see it today, by 1942. The new building is built in greek revival style and is under the ownership of the council. Today it is used for everything from tai chi to playgroups.

Glengarry Mechanics’ Institute

The Institute was established in 1886 and the current building dates to the 1920s. Glengarry began as a library and was much used with hundreds of people visiting the library every year in the 1800s. When the new hall was opened in 1920, it was moved across the road, it was used as a library, a picture theatre, and by many local organisations. The hall had reached a fairly degraded state, on the outside, by 2013 and funding was raised to restore the outside including the hall roof which was in a perilous state. It is still used extensively by the community today.

The Institute was established in 1886 and the current building dates to the 1920s. Glengarry began as a library and was much used with hundreds of people visiting the library every year in the 1800s. When the new hall was opened in 1920, it was moved across the road, it was used as a library, a picture theatre, and by many local organisations. The hall had reached a fairly degraded state, on the outside, by 2013 and funding was raised to restore the outside including the hall roof which was in a perilous state. It is still used extensively by the community today.

Longwarry Public Hall

The Longwarry Public hall, formerly Longwarry Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library, was established in 1886, and the first building built in 1889, though the current building dates mainly to the 1950s. Longwarry operated as a free library and lecture hall as well as being the home of the local brass band and health centre in the 1800s and early 1900s. The hall burnt down in the 1950s and the hall you see today was constructed, it was opened in 1953 with additions in the 1960s. In 2009 it was significantly upgraded including a new roof. It is still used by many community groups and an old time dance has been running every Monday evening and every fourth Saturday since, roughly, 1900.

The Longwarry Public hall, formerly Longwarry Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library, was established in 1886, and the first building built in 1889, though the current building dates mainly to the 1950s. Longwarry operated as a free library and lecture hall as well as being the home of the local brass band and health centre in the 1800s and early 1900s. The hall burnt down in the 1950s and the hall you see today was constructed, it was opened in 1953 with additions in the 1960s. In 2009 it was significantly upgraded including a new roof. It is still used by many community groups and an old time dance has been running every Monday evening and every fourth Saturday since, roughly, 1900.

Malmsbury Mechanics’ Institute

Founded in 1862, the current building dates to 1876. This is the original Malmsbury building though. Due to various factors, including lack of funds and council involvement, the building wasn’t completed till 1876 despite the institute being founded years earlier. Malmsbury was still functioning as a Mechanics’ Institute in 1919, including a library, but by World War II the building had largely fallen into disuse and for a while it was used as a bank branch. The Shire now owns the building and it is the home of the historical society, as well as various community events.

Meeniyan Hall

Meeniyan Hall, formerly Meeniyan Mechanics’ Institute, was established in 1892, but the current building dates to 1939. The hall was never a library and it was mainly used for visiting entertainers and for music lessons. The building burnt down in 1938, but a new hall was built and opened in 1939. It was used for local dances in 1960s often holding as many as 600 people. It is currently used for a wide variety of community programs, including the inaugural Meeniyan Garlic Festival in 2017. The hall was the home of the Garlic institute and you can see the crowds attracted in the photo above.

Melbourne

The earliest Mechanics’ Institute in Melbourne. The Melbourne Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1839 and the current building dates to 1886. The original library, and collection of scientific specimens, was housed in rented accommodation. A permanent hall was built in 1842, but the programs offered including: entertainments, political and business meetings, social gatherings and church services proved to be so popular that it was decided that a bigger building was needed. The funds weren’t found until the 1870s and in 1872 the new facilities were opened, including a 100 foot long hall and significant space for the library upstairs. At the same time it was decided to change the name to the Melbourne Athenaeum. In 1886 the building was significantly remodelled, including the facade, which you can see today. In the early 1900s it was determined that a theatre was needed and the Athenaeum Theatre, built inside the old hall, was completed in 1924. The theatre is still very much in use today by acts from all over the world and is one of Melbourne’s most popular venues. The library is also still in existence and runs as a subscription library. You can search their collection here.

Port Fairy Library and Lecture Hall

Founded in 1860 and the current building dates to 1865. A library was functioning in Belfast, as it was then known, as early as 1856 but an institute wasn’t officially formed until 1860. In 1864 land was granted by James Atkinson to build a library for Belfast and it has remained in the same position since it was opened in 1865. The Lecture Hall next door was also opened at roughly the same time. The library is now used as the public library, after 120 years of independent operation it joined the Corangamite Shire libraries in 1981. The lecture hall is used by lots of community groups including the local theatre group and the spring festival.

Founded in 1860 and the current building dates to 1865. A library was functioning in Belfast, as it was then known, as early as 1856 but an institute wasn’t officially formed until 1860. In 1864 land was granted by James Atkinson to build a library for Belfast and it has remained in the same position since it was opened in 1865. The Lecture Hall next door was also opened at roughly the same time. The library is now used as the public library, after 120 years of independent operation it joined the Corangamite Shire libraries in 1981. The lecture hall is used by lots of community groups including the local theatre group and the spring festival.

Prahran Mechanics’ Institute.

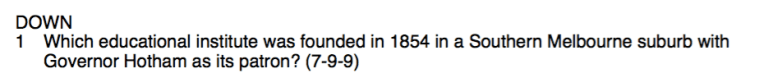

The Prahran Mechanics Institute was founded in 1854 though the building they currently reside in, a converted 1960s fabric factory, was not their home until 2015. The original building was in Chapel Street and is still owned by the institute, though it is rented out as shops.

The PMI started as a lending library and as an institute for education and lectures. Due to a dispute with the the Secretary/Librarian in the mid 1800s (he wouldn’t vacate the building and the roof of the institute was removed to force him to leave) and the neglect of another secretary/librarian in the late 1800s the PMI building was rebuilt onsite in 1900. However there was not enough space, so in 1915 they moved to High Street in Prahran, also starting the Prahran Technical School (this building can be seen in the photo above). In the 1980s a decision was made to move away from being simply a general collection library to being a library which specialised in Victorian history.

This specialisation continues today with the PMI holding a collection of over 30 000 books and being dedicated to preserving the history of Victoria. In 2009 space was desperately need for the rapidly expanding collection. So the PMI sought to end the 99 year peppercorn lease which allowed to Minister for Education to use the buildings that formerly held the Prahran Technical School, which was now being used by Swinburne University. The Minster agreed to relinquish the lease if the PMI sold their High Street building to Swinburne University. They did and moved around the corner to St Edmonds Road into a more modern building with the extensive space that the collection needed (you can see the exterior and interior of the new building in the photos above). The PMI is still functioning under its original rules and incorporation and is the only Mechanics’ Institute in Victoria which has its own Act of Parliament for its incorporation. It is run by a committee with four professional staff running the library. You can check out their catalogue here

Rosedale Mechanics’ Institute Hall

The Rosedale Mechanics’ Institute was established in 1863 and the current building dates to 1874. Rosedale began operating in 1868 in rented premises and the original form of the current building was built in 1874 after being designed by William Allen. Rosedale was originally called The Mechanics’ Institute and Library and Scientific Association. It contained a surprisingly large hall, a stage, a supper room, several meeting rooms and a library. The stage was removed at some point and an extension with toilets added in roughly the 1950s. The hall was also extended fairly early in the process, you can see the addition in the photo above, and much later a floating ceiling was added. The hall used to house the public library, but it was moved. It is now home to the op shop and is used by community groups.

Stratford Mechanics’ Institute.

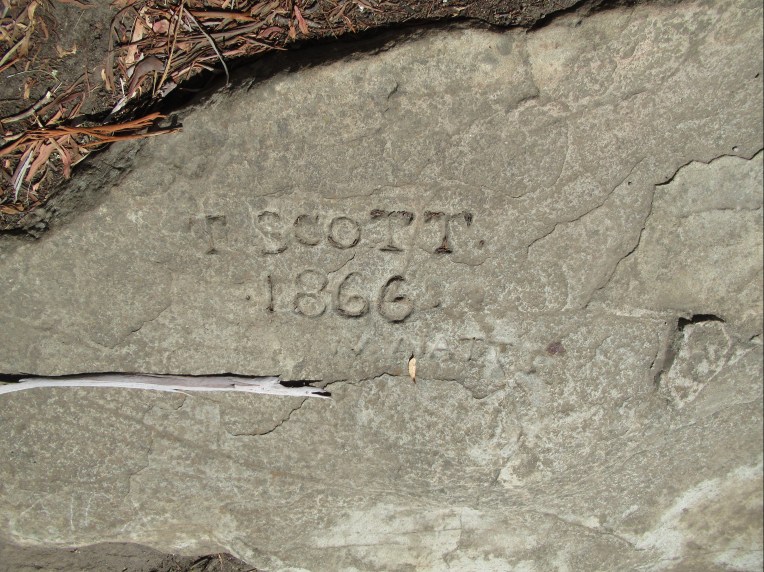

The Stratford Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1866 and the current building was constructed in 1888. When it was originally founded Stratford lapsed very quickly and another attempt to form a Mechanics’ Institute was tried in 1874, which didn’t work either. However, by 1882 a committee was formed and the library was set up in the shire hall and books bought. By 1888 they’d built the existing hall. In the 1950s a spectacularly ugly addition was built on the beautiful 1800s facade. It mainly housed toilets. In the early 2000s, through fundraising and government grants, the hall was restored to its former 1800s glory. It is run by an active committee and is the home to many local events, including the parts of the Stratford Shakespeare festival.

The Stratford Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1866 and the current building was constructed in 1888. When it was originally founded Stratford lapsed very quickly and another attempt to form a Mechanics’ Institute was tried in 1874, which didn’t work either. However, by 1882 a committee was formed and the library was set up in the shire hall and books bought. By 1888 they’d built the existing hall. In the 1950s a spectacularly ugly addition was built on the beautiful 1800s facade. It mainly housed toilets. In the early 2000s, through fundraising and government grants, the hall was restored to its former 1800s glory. It is run by an active committee and is the home to many local events, including the parts of the Stratford Shakespeare festival.

Toongabbie Mechanics’ Institute.

Toongabbie Mechanics’ Institute was established in 1883 and the building you see today was also constructed in 1883. It was a fascinating example of a two story weatherboard construction from this period. The second story was a 1890s rear extension. The hall contains a stage, where many local performances were held, and was home to a library. There are also a number of smaller rooms in the two story extension. It was used as the local Court of Petty Sessions and as a bank. By 1983 the building was in extremely poor condition and it had been suggested that burning it down was the best option. Thankfully the local community rallied and with government funding it was saved. Now it is used for everything from weddings, to school concerts, to old time dances.

Trafalgar Public Hall

The Trafalgar Public Hall, formerly the Trafalgar Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library, was founded in 1889, though the current building dates to 1935. The original hall operated as free library and it was rebuilt in 1908 when it became the home of the Naracan Shire. The hall became the focus of the community with traveling shows performing there and it was used as a library and a dance hall. The hall and all its contents were destroyed in a massive fire in 1934 and a new hall was finished by 1935. The new hall contained a bio cabin for the showing of movies. There was also a library, but by 1957 this had become a kiosk, and by 1964 a ladies toilet. The hall was used for everything from badminton to school concerts and is now the home of the local amateur dramatic society as well a number of other community uses including weddings and family reunions.

So that’s the end of my collection of Mechanics’ Institute photos and information. As I stated, this is by no means anywhere near all the Mechanics’ Institutes in Victoria and they can be found in other states as well as all over the United Kingdom and in Canada and America. As a concept they are a fascinating example of communities helping themselves and coming together. Even if many of the institutes themselves don’t survive today the halls are still very much at the heart of the community.

References.

Site visits, 2017, 2016 and 2015.

http://www.pmi.net.au/home/timeline/

http://www.pmi.net.au/home/mihistory/

http://home.vicnet.net.au/~mivic/

http://www.melbourneathenaeum.org.au/

http://www.berwickmilibrary.org.au/

These Walls Speak Volumes: A history of Mechanics’ Institutes in Victoria by Pam Baragwanath and Ken James ISBN: 9780992308780 you can borrow it from the Prahran Mechanics’ Institute Victorian History Library here library.pmi.net.au/fullRecord.jsp?recno=23726

The photos are all mine.

Disclaimer: I work at the PMI Victorian History Library.

And the gargoyles.

And the gargoyles. All buildings should have at least one gargoyle.

All buildings should have at least one gargoyle.

The columns and brackets are cast iron which were made in a foundry in Carlton. They were covered with canvas, fixed with white lead and cement and had five coats of oil paint. The ceiling was hand painted and gilded. In the centre of each panel are the shields and arms of England, Scotland and Australia as well as the arms of the bank and the arms of the main cities in which it operated.

The columns and brackets are cast iron which were made in a foundry in Carlton. They were covered with canvas, fixed with white lead and cement and had five coats of oil paint. The ceiling was hand painted and gilded. In the centre of each panel are the shields and arms of England, Scotland and Australia as well as the arms of the bank and the arms of the main cities in which it operated. The details on the walls are truly impressive

The details on the walls are truly impressive The beautiful tiled floor is not original but it was based on the original colours and patterns.

The beautiful tiled floor is not original but it was based on the original colours and patterns. There is also a magnificent stained glass window. Up the very top you can see a miner ‘panning off’ which is meant to represent the origins of the wealth of Victoria. The central figure is a woman representing ‘labour’. The window also depicts the coats of arms of both Britain and Australia and symbols of the four divisions of the globe.

There is also a magnificent stained glass window. Up the very top you can see a miner ‘panning off’ which is meant to represent the origins of the wealth of Victoria. The central figure is a woman representing ‘labour’. The window also depicts the coats of arms of both Britain and Australia and symbols of the four divisions of the globe.

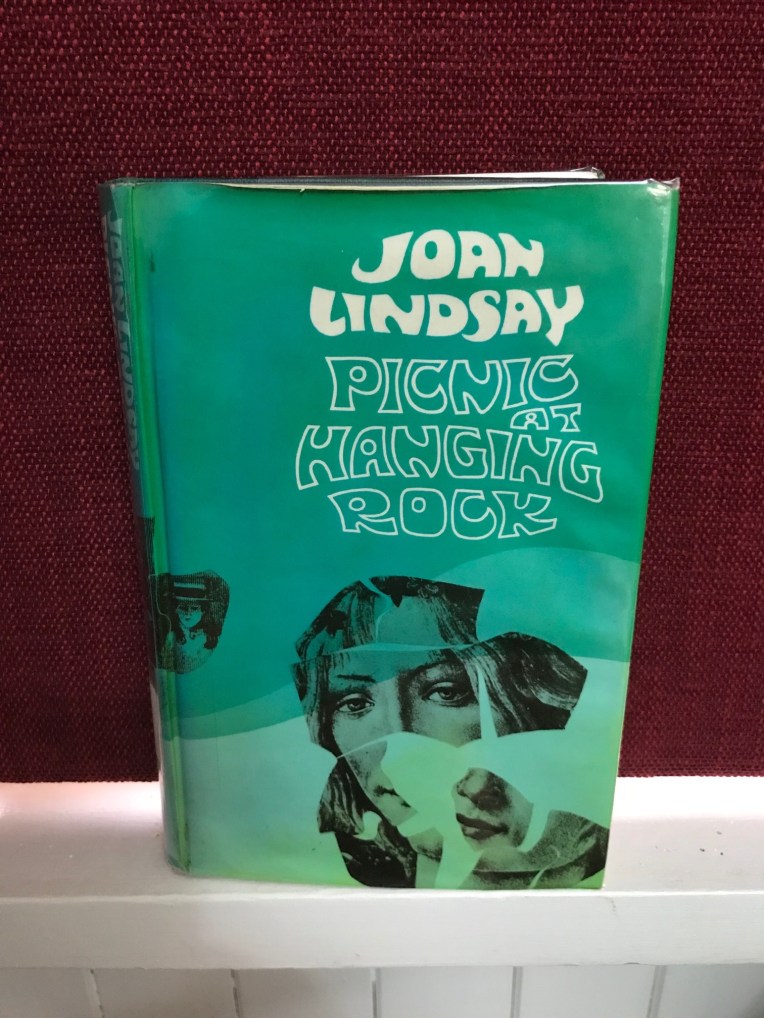

And it continues to hold a fascination that goes beyond the book and the film. It is a truly majestic place.

And it continues to hold a fascination that goes beyond the book and the film. It is a truly majestic place.

The stain glass window dedicated to St Thomas also carried a dedication for the A’Beckett family on its base

The stain glass window dedicated to St Thomas also carried a dedication for the A’Beckett family on its base The A’Becketts were a prominent district family and the font is also dedicated to one of their number.

The A’Becketts were a prominent district family and the font is also dedicated to one of their number.

Port Fairy’s Griffiths Island is now connected to the mainland by a causeway,

Port Fairy’s Griffiths Island is now connected to the mainland by a causeway,  But in the 1800s the island was only accessible by boat and it was often dangerously rough so was cut off completely from the mainland. It was extremely isolated. The island was originally 3 islands, Rabbit (on which the light house stands), Goat and Griffiths. They have joined together as one island, partly from coastal erosion and partly from the construction that surround the islands. They serve to protect the entrance to Port Fairy. Rabbit island would have been extremely remote in the 1800s.

But in the 1800s the island was only accessible by boat and it was often dangerously rough so was cut off completely from the mainland. It was extremely isolated. The island was originally 3 islands, Rabbit (on which the light house stands), Goat and Griffiths. They have joined together as one island, partly from coastal erosion and partly from the construction that surround the islands. They serve to protect the entrance to Port Fairy. Rabbit island would have been extremely remote in the 1800s.

The Mechanics’ Institute dates to 1905, but the current building was built in 1942. The hall was used for everything from ANZAC celebrations to rollerskating. The hall burnt down in 1940 but it was rebuilt, as you can see it today, by 1942. The new building is built in greek revival style and is under the ownership of the council. Today it is used for everything from tai chi to playgroups.

The Mechanics’ Institute dates to 1905, but the current building was built in 1942. The hall was used for everything from ANZAC celebrations to rollerskating. The hall burnt down in 1940 but it was rebuilt, as you can see it today, by 1942. The new building is built in greek revival style and is under the ownership of the council. Today it is used for everything from tai chi to playgroups.

The Institute was established in 1886 and the current building dates to the 1920s. Glengarry began as a library and was much used with hundreds of people visiting the library every year in the 1800s. When the new hall was opened in 1920, it was moved across the road, it was used as a library, a picture theatre, and by many local organisations. The hall had reached a fairly degraded state, on the outside, by 2013 and funding was raised to restore the outside including the hall roof which was in a perilous state. It is still used extensively by the community today.

The Institute was established in 1886 and the current building dates to the 1920s. Glengarry began as a library and was much used with hundreds of people visiting the library every year in the 1800s. When the new hall was opened in 1920, it was moved across the road, it was used as a library, a picture theatre, and by many local organisations. The hall had reached a fairly degraded state, on the outside, by 2013 and funding was raised to restore the outside including the hall roof which was in a perilous state. It is still used extensively by the community today. The Longwarry Public hall, formerly Longwarry Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library, was established in 1886, and the first building built in 1889, though the current building dates mainly to the 1950s. Longwarry operated as a free library and lecture hall as well as being the home of the local brass band and health centre in the 1800s and early 1900s. The hall burnt down in the 1950s and the hall you see today was constructed, it was opened in 1953 with additions in the 1960s. In 2009 it was significantly upgraded including a new roof. It is still used by many community groups and an old time dance has been running every Monday evening and every fourth Saturday since, roughly, 1900.

The Longwarry Public hall, formerly Longwarry Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library, was established in 1886, and the first building built in 1889, though the current building dates mainly to the 1950s. Longwarry operated as a free library and lecture hall as well as being the home of the local brass band and health centre in the 1800s and early 1900s. The hall burnt down in the 1950s and the hall you see today was constructed, it was opened in 1953 with additions in the 1960s. In 2009 it was significantly upgraded including a new roof. It is still used by many community groups and an old time dance has been running every Monday evening and every fourth Saturday since, roughly, 1900.

Founded in 1860 and the current building dates to 1865. A library was functioning in Belfast, as it was then known, as early as 1856 but an institute wasn’t officially formed until 1860. In 1864 land was granted by James Atkinson to build a library for Belfast and it has remained in the same position since it was opened in 1865. The Lecture Hall next door was also opened at roughly the same time. The library is now used as the public library, after 120 years of independent operation it joined the Corangamite Shire libraries in 1981. The lecture hall is used by lots of community groups including the local theatre group and the spring festival.

Founded in 1860 and the current building dates to 1865. A library was functioning in Belfast, as it was then known, as early as 1856 but an institute wasn’t officially formed until 1860. In 1864 land was granted by James Atkinson to build a library for Belfast and it has remained in the same position since it was opened in 1865. The Lecture Hall next door was also opened at roughly the same time. The library is now used as the public library, after 120 years of independent operation it joined the Corangamite Shire libraries in 1981. The lecture hall is used by lots of community groups including the local theatre group and the spring festival.

The Stratford Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1866 and the current building was constructed in 1888. When it was originally founded Stratford lapsed very quickly and another attempt to form a Mechanics’ Institute was tried in 1874, which didn’t work either. However, by 1882 a committee was formed and the library was set up in the shire hall and books bought. By 1888 they’d built the existing hall. In the 1950s a spectacularly ugly addition was built on the beautiful 1800s facade. It mainly housed toilets. In the early 2000s, through fundraising and government grants, the hall was restored to its former 1800s glory. It is run by an active committee and is the home to many local events, including the parts of the Stratford Shakespeare festival.

The Stratford Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1866 and the current building was constructed in 1888. When it was originally founded Stratford lapsed very quickly and another attempt to form a Mechanics’ Institute was tried in 1874, which didn’t work either. However, by 1882 a committee was formed and the library was set up in the shire hall and books bought. By 1888 they’d built the existing hall. In the 1950s a spectacularly ugly addition was built on the beautiful 1800s facade. It mainly housed toilets. In the early 2000s, through fundraising and government grants, the hall was restored to its former 1800s glory. It is run by an active committee and is the home to many local events, including the parts of the Stratford Shakespeare festival.

Port Fairy is a town in Western Victoria that was founded as a town in 1843. There were settlers in the area before this date, and the current name for the town comes from the ship the Fairy which is believed to have arrived in the area in c.1828. The area was also regularly visited by whalers and sealers. The date of 1843 comes from the special survey which was granted to James Atkinson at that time. The special surveys were a system where the government of the Colony of New South Wales was able to control ownership of the land in the Port Phillip District. This was well before federation of Australia as a country in 1901, but also before Victoria became a colony independent from New South Wales which happened in 1851. The basic premise behind the special survey system was to stop squatters just claiming land, because when they did there was little ability to regulate it and there was no fee for the government.

Port Fairy is a town in Western Victoria that was founded as a town in 1843. There were settlers in the area before this date, and the current name for the town comes from the ship the Fairy which is believed to have arrived in the area in c.1828. The area was also regularly visited by whalers and sealers. The date of 1843 comes from the special survey which was granted to James Atkinson at that time. The special surveys were a system where the government of the Colony of New South Wales was able to control ownership of the land in the Port Phillip District. This was well before federation of Australia as a country in 1901, but also before Victoria became a colony independent from New South Wales which happened in 1851. The basic premise behind the special survey system was to stop squatters just claiming land, because when they did there was little ability to regulate it and there was no fee for the government.

He died in 1862 at the age of 40 and the tomb reads:

He died in 1862 at the age of 40 and the tomb reads:

There are more people buried in the cemetery than are known about. Many of the early burials would have been laid to rest under simple wood crosses and these simply wouldn’t have survived the harshness of Port Fairy’s coastal weather. Despite this, the surviving burials provide a fascinating record of the life and death of the early inhabitants of the district.

There are more people buried in the cemetery than are known about. Many of the early burials would have been laid to rest under simple wood crosses and these simply wouldn’t have survived the harshness of Port Fairy’s coastal weather. Despite this, the surviving burials provide a fascinating record of the life and death of the early inhabitants of the district. Tower Hill itself is a former volcano not far from Port Fairy and about 3 hours drive west of Melbourne. You can see the view looking over the remains of the Tower Hill crater and looking out towards the sea from the top of Tower Hill in the photos below.

Tower Hill itself is a former volcano not far from Port Fairy and about 3 hours drive west of Melbourne. You can see the view looking over the remains of the Tower Hill crater and looking out towards the sea from the top of Tower Hill in the photos below.

The epitaph reads

The epitaph reads

The site of Robert Henry Woodward’s original grave at

The site of Robert Henry Woodward’s original grave at

Herb Garden Melbourne Botanic Gardens.

Herb Garden Melbourne Botanic Gardens.