It’s been a while, life, work and other writing are basically the reasons. But I’m hoping to get back into a slightly more regular blog schedule, as there’s a backlog of, I hope, interesting things I want to write about. But back to the buried village. The village in question is Te Wairoa, just out of Rotorua on Aotearoa New Zealand’s North Island. The remains of the village sit in a really beautiful dip in a complex volcanic landscape. The map below gives you an idea of both the location of the village and the volatility of the landscape

As you might have gathered from the name, the fate of the village is not a happy one, but although one night of 1886 saw the end of the village, it did have a beginning. So we’re going to start there.

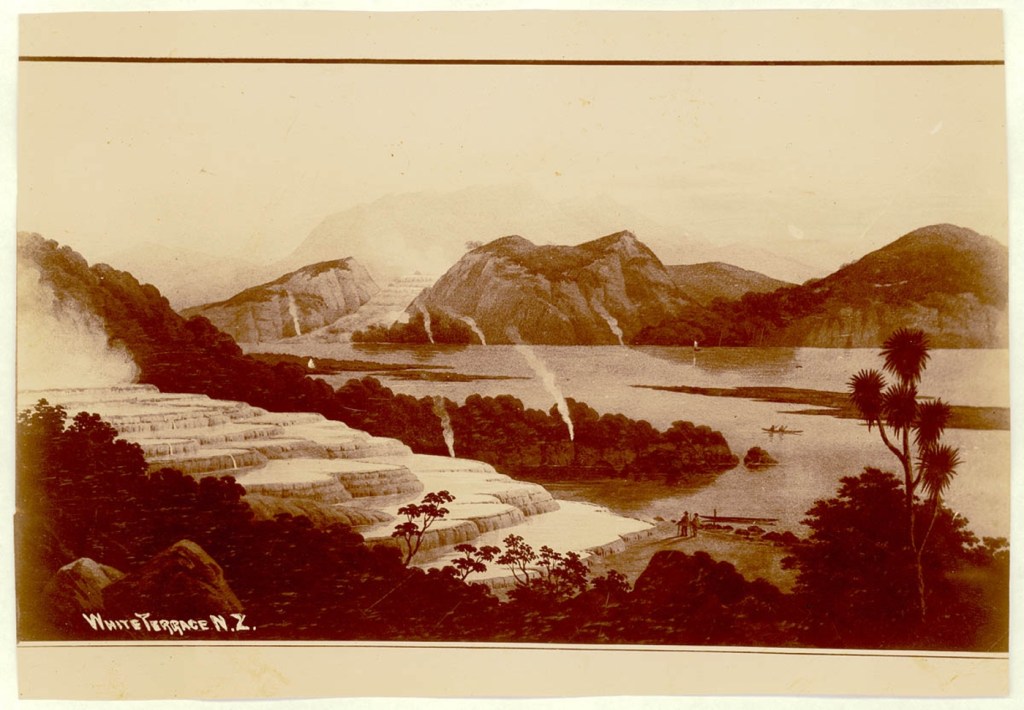

Maori people had been living in the area for generations, but Europeans moved into the area in the early 1800s. The foundations of the town itself are actually, interestingly, rooted in tourism. In the 1850s the local Tarawera iwi began guiding tourists to the magnificent Pink and White Terraces. A tradition that continues with the thermal landscape around Rotorua today. The guides were mainly women, including Guide Sophia who was described as an intelligent and pleasant woman and who bore 15 children. And Guide Kate, who was described as Amazonian. The Pink and White Terraces were extraordinary geological formations of hot and cold sinter baths, described as the 8th wonder of the world. You can see contemporary images of them below.

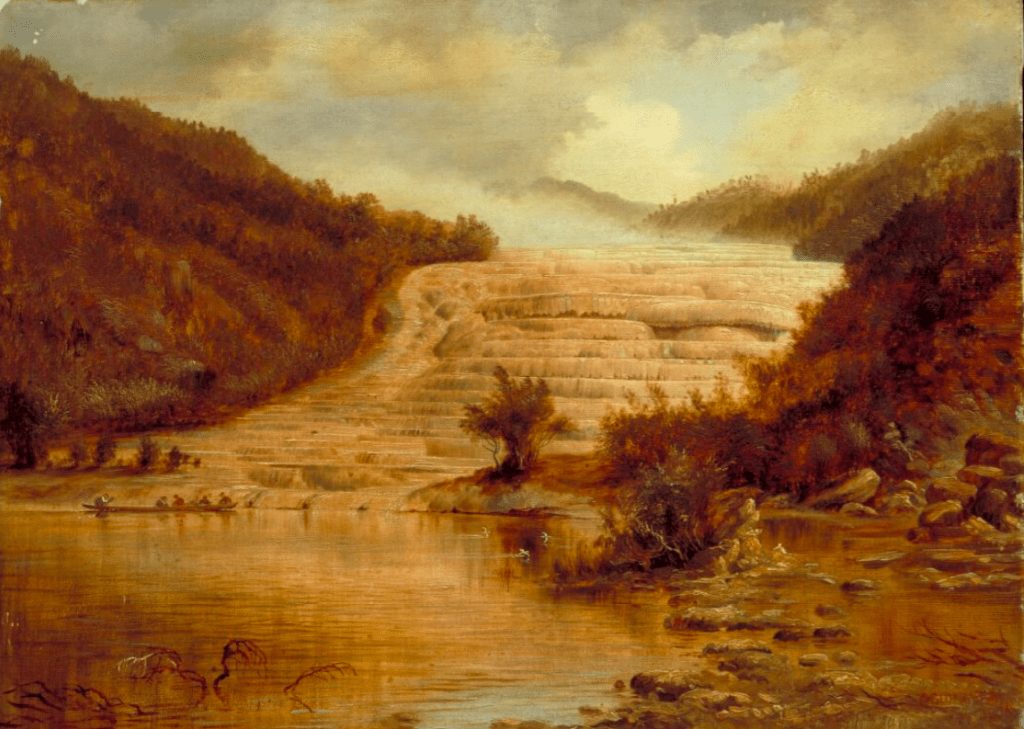

Victorians (the era not the state) came over long distances to visit these terraces. They were formed over 600 years ago when silica rich residue called sinter, originating from geysers, cascaded down and left thick silica deposits which, when they cooled, built these giant staircases as well as large pools of clear water. The White Terraces were about 280 metre wide and 30 m high, the Pink Terraces were a bit smaller and their colour came from the feric rich waters. You can get an idea of the colour in the painting below.

Objects became petrified by these silica rich waters. You can see a petrified hat below, that maybe a tourist left behind.

Some of the items were intentionally petrified for the tourists, including this toy cot and dog made out of newspaper.

By the 1880s Te Wairoa itself had become the hub of this tourist trade, boasting two hotels: McRae’s Rotomahana Hotel and the unliscenced Terrace Hotel. The village was home to Maori and Europeans and included a school, a church, a meeting house, blacksmith’s, a store, flour mill and houses and whares (Maori dwelling – usually steep roofed). You can see it in the image below.

As you’ll see in the caption above, this was Te Wairoa before the eruption. Which brings us to the night of the June 9th 1886. There were warnings : on May 31st the creek was suddenly dry and then water surged filling the creek towards the lake, but then quickly drained away again. This was noted by Guide Sophia as she led tourists out to the lake. Then when they were crossing the lake in a boat towards the terraces, European and Maori people on the boat saw a Maori waka (war canoe) bigger than any known on the lake, and the men rowing the waka didn’t respond to any calls, so they were thought to be spirits. When the boat arrived at the Pink Terraces they found that a geyser had ejected mud much further than usual. These all together provoked unease across the valley, but there wasn’t really anything that could be done.

All remained calm until the 9th of June.

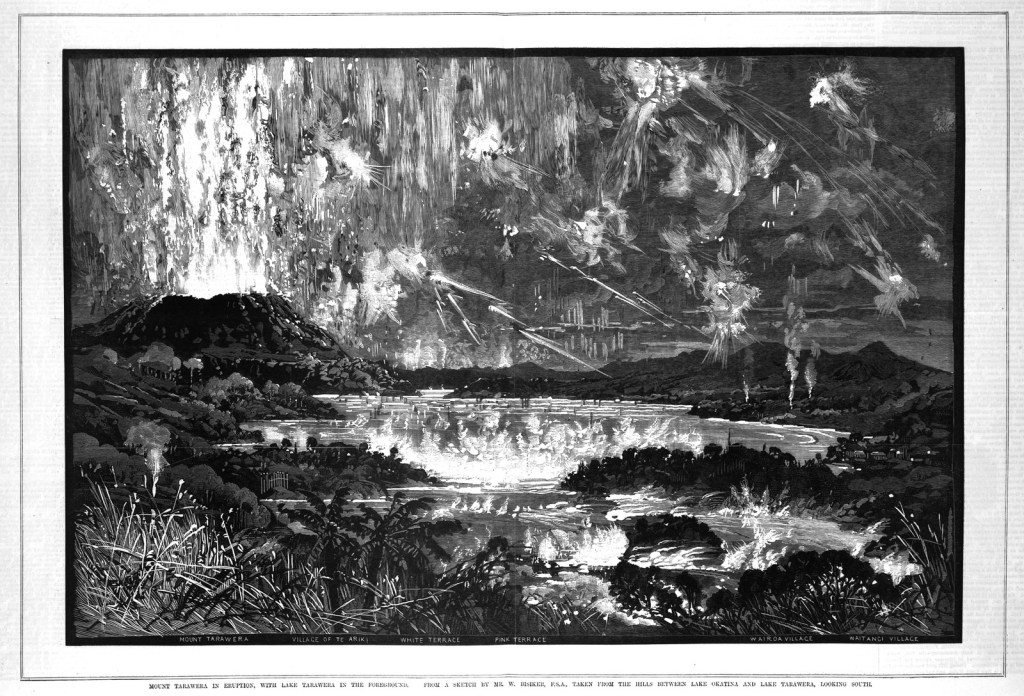

Shortly before midnight the earthquakes began. By 2:30 am craters were starting to open and erupting with larva along an 8 km rift north east towards the lake. A vast column of ash 9.5 km high rose from the direction of Lake Tarawera, there was a freezing wind, roaring and an eerie red glow. By about 3:20 the destruction had spread. Violent steam eruptions (when molten rock encountered water) sent ash and mud into the sky that blanketed the surrounding area. Debris continued to fall until about 6:00 am and when the dust has settled, the villages of Te Ariki, Moura, Tokiniho, Totarariki, Rotomahana and Waitngongongo were either buried completely or had been on the site of active craters, there were no survivors. In Te Wairoa much of the town was buried and 17 people killed, though amazingly most of the people managed to escape. The landscape was was irrevocably changed. Not only were the Pink and White Terraces obliterated, there was a 16 kilometre rift across the mountain from Tarawera that had opened into the Waimangu valley. You can see the valley below, all the vegetation, apart from a few of the larger trees, has grown since the 1886 eruption.

The eruption was felt all over Aotearoa New Zealand. In nearby Rotorua new hot springs opened up, jets of steam issued from the rocks and geysers spurted along the shore edge of Lake Rotorua. Many people thought the world was ending. You can see a near contemporary painting of the eruption below.

It really gives a sense of the extreme violence. More than 150 people were killed in the eruption, as well as kilometres of land devestated. For the local Tuhorangi, Maori, it also meant the destruction of the remains of their ancestors, many of whom had been entombed on the mountain itself. Most of the victims of the eruption were also Maori.

As the eruption settled rescue groups went out from Rotorua and Ohinemutu to try to find survivors, they met with limited success, especially in the towns closest to the eruption. The higher survival rate in Te Wairoa, though most of the town itself was buried, was partly because it was a little further from the eruption so it wasn’t immediately subsumed. About fifty people made it through the flaming debris to Guide Sophia’s whare, the sloped roof meant that the debris slid off rather than collecting like they did on the European houses and hotels. This meant that the whare stayed standing where as the European buildings collapsed under the weight. This was also true of the Hinemihi meeting house. Of the 17 people who died in the town some died outside, either struck by debris or suffocated from the ash, or they died inside collapsed or burnt buildings.

We have some incredible first hand accounts of the eruption, for example Mr McCrae from the Roromahana Hotel described it as. “We saw a sight that no man who saw it can ever forget. Apparently the mount had three craters, and flames of fire were shooting up fully a thousand feet high. There seemed to be a continuous shower of balls of fire for miles around.” McRae and his guest, staff and several other locals made their way to Guide Sophia’s whare, and all, apart from the one tourist Edwin Bainbridge, survived. Bainbridge died when the hotel’s balcony fell on him when they were trying to escape.

After the eruption no one recieved any government compensation for their destroyed buildings, and insurance companies refused to pay out because people were not covered for volcanic eruption. Ultimately Te Wairoa was abandoned and left buried. It has been the site of a number of archaeological digs over the years, with many 19th century artefacts recovered that paint a picture of life in the lost village.

The last image above is testament to the power of the eruption. It’s a chain found on the site that might have been used to secure the blacksmith’s, it is completely encrusted with volcanic mud which has bound it all up into one solid clump

As part of the digs over the years, sections of the village have been unearthed and can also be explored now. What’s most striking about them for me is just how layered and solid the mud is. It’s hard to imagine that it wasn’t always there.

The last two photos are the remains of stone pataka (store house), it would have been lined with ferns and rushes and used to store potatoes and other crops. It was actually one of the first pieces of the village excavated, a woman called Vi Smith was picnicking beside the stream in the early 1930s and she noticed a stone in the bank and scraped back to the mud to reveal one of the carved stones.

The remains of the buried buildings are not the only artefacts that you can see at the Te Wairoa site. There’s other, in some ways, more unsual items. Including the below carronade. It was found in the stream in the 1930s at the bottom of the waterfall (I’ll come back to the waterfalls in a moment). It’s thought it was brought to Te Wairoa from the coast by the Maori as possible defence against another tribe in the 1860s.

Another interesting artefact is the bow section of the waka tuau, which would have been 30 feet originally. It was used originally in the invasion of the Lake District in early 1800s but, after the invasion, it was used for conveying tourists on Lake Tarawera. Its remains were uncovered below the waterfalls in 1927

The final really interesting artefact was the remains of some wooden posts. This might seem like an odd one, but this row of poplar fence posts survived the eruption with just their tops poking out of the mud. The posts then sprouted and, over the next 126 years, 30 to 40 of them grew to roughly 40 metres. The trees sadly began to fall down from 2010 onwards, and were eventually felled in the late 2010s. You can still see the area where they grew though

The Tarawera eruption was utterly devastating to the landscape, but what feels almost counter intuitive when you’re visiting is how quiet and lush and peaceful the landscape is now. The native bush has magnificently colonised the ‘new’ landscape created by the eruption. And nowhere is this more evident that around the beautiful waterfalls, you can see on the river walk right next to the remains of Te Wairoa.

The story of Te Wairoa and the Mount Tarawera eruption is not complete. Mount Tarawera is still an active volcano that is part of a very active volcanic landscape. Tarawera has erupted at least five times in the last 20,000 years, and the 1886 eruption was actually small compared to earlier eruptions. There is in fact a high likelihood that there will be another larger eruption, the only question really is when, and it may not be for thousands of years. Scientists monitor the volcano and the area for precursors like earthquakes, ground deformation and new or increasing hot spring flow, but ultimately, as with all volcanoes, if another eruption does happen we are as at the mercy of the volcano now as we were in 1886. It’s a landscape that really makes you think.

References:

Site visit 2024 – a lot of the information has come from the excellent signs in the buried village itself

https://www.buriedvillage.co.nz/

https://www.waimangu.co.nz/history/mount-tarawera/

https://www.newzealand.com/au/feature/mount-tarawera/

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/eruption-mt-tarawera

https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/the-night-tarawera-awoke/

Images:

The photos and video are all mine.

Pink Terraces : State Library of NSW : https://search.sl.nsw.gov.au/permalink/f/1cvjue2/ADLIB110317253

White Terraces: State Library of Victoria

https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/156d4cp/alma9939648455207636

White Terraces with the Pink Terraces in the background: State Library of NSW

https://search.sl.nsw.gov.au/permalink/f/1cvjue2/ADLIB110317254

Pink Terraces demonstrating the colour: National Library of Australia

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-134305524/view

Te Wairoa before the eruption : Te Papa

https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/1267698

Mount Tarawera eruption: State Library of Victoria

https://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/258258

I run this blog because I enjoy it, but if you felt able to contribute towards its upkeep I’d appreciate it.