To write about the Magna Carta is to tread already very well trodden ground. For a document that had little immediate impact, its mythology has echoed down the centuries.

I am not intending to write anything ground breaking or revelatory about the Magna Carta. This post is going to draw together my experiences with people and sites that hold together the thread of the history of the Magna Carta and explore the outline and background of the document’s story.

My interest in the Magna Carta began in year eleven at high school. As an Australian I didn’t get much of a chance to write about medieval history within the curriculum, but in year eleven we got to chose our own research project and I picked the Magna Carta. It was the first time I got to seriously research the medieval period and I still remember the pride with which I produced my 2000 word report. It only covered the basics, but it was a first step on a path that in many ways has ultimately led to this blog.

I’ve always found the Magna Carta interesting, because despite the reality of its actual contents it has come to be a symbol of Western style democracy. The Magna Carta was sealed (not signed) on June 15th 1215. It didn’t come out of nowhere, it was based on other charters from both England and the continent, but its legacy has been peculiarly enduring. The Rights of Man from the French Revolution are based on it, as is the American Bill of Rights and the UN Declaration of Human Rights. It is held up as a bastion of freedom against tyranny. All of this, I discovered when I began to research as a seventeen year old, has very little basis in the reality of the document.

The Magna Carta contains 63 clauses. Covering everything from fish weirs in the Thames and the Medway, to how heirs should be handled, to how specific people are to be treated. The two clauses that give the Magna Carta its formidable reputation at 39 and 40.

(39) No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.

(40) To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.

These are proud words, but at the time (like the rest of the Charter) they had little to no effect. Apart from any other reason the Charter was repealed by the Pope by September 1215 and the rebel barons were excommunicated. It wasn’t until the Magna Carta was reissued in 1217 and 1225, under Henry III, and when it first came into the King’s Statute Books, in the reign of Edward I in 1297, that it began to have any real impact. Even so you only have to look at the rest of English history (the War of the Roses and the Tudors for example) to show much effect it had on the power of kings to summarily imprison their subjects.

The Magna Carta was by the Barons for the Barons. It is an excellent reflection of what was concerning the nobility in 1215. It is worth remembering that none of the the clauses are given more importance than any other: fish weirs are just as important as not delaying justice. The Magna Carta was extracted from John under duress in an attempt to shore up their own authority. It was never intended to be catch all for every person and it is important to remember that it is a document born of war.

The conflict between King John and his barons was not one that was singular to John. His brother and father before him had all dealt with rebellious barons. It was under John however that it all came to a head in a perfect storm. A lot, but not all, of which was John’s fault. He took the throne in 1199 and it began badly as there was dispute over whether the throne should have gone to Arthur Duke of Brittany, the son of John’s dead elder brother Geoffrey. This was mainly important on the continent as Arthur was seen as a French puppet by many of the English.

Many of John’s failings in kingship were personal. He was inconsistent and could be very vindictive. Additionally after he lost the majority of the Plantagenet lands on the continent he had time to focus squarely on England, which the barons didn’t appreciate. It also didn’t help that he succeeded in having the whole country placed under interdict because he wouldn’t accept the Pope’s candidate as Archbishop of Canterbury. He was essentially bad at managing people and extremely suspicious. Even taking into account chronicler’s bias most contemporary accounts are reasonably consistent on John’s failings.

This led to revolt and ultimately in the Barons offering Prince Louis of France the English throne.

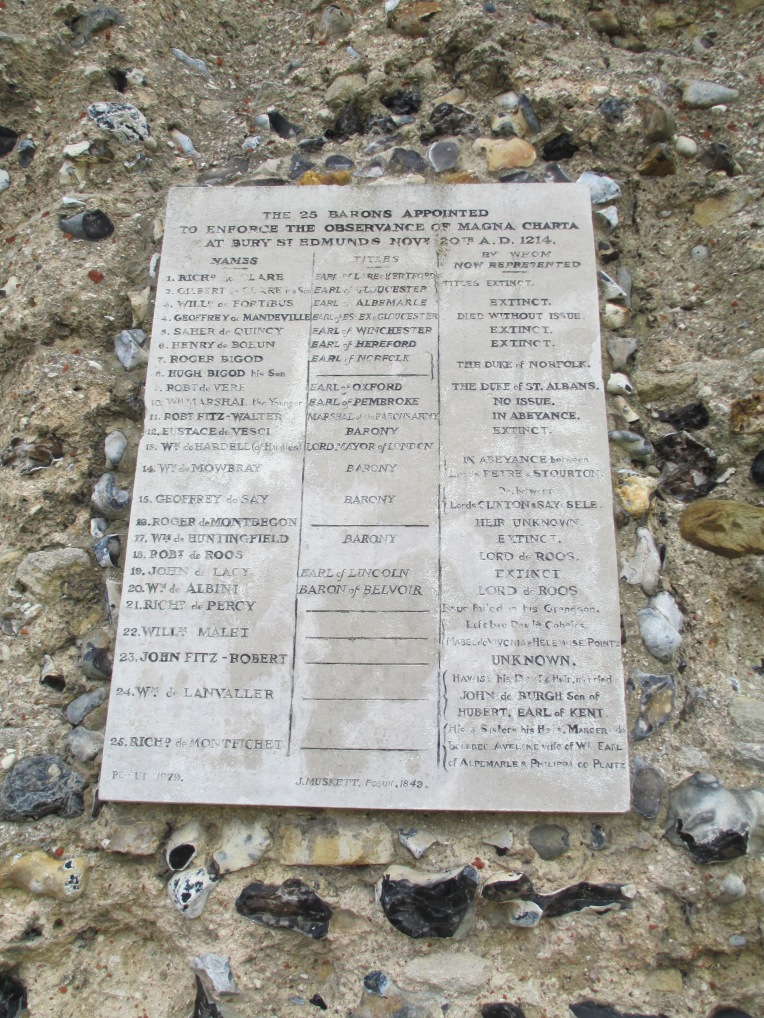

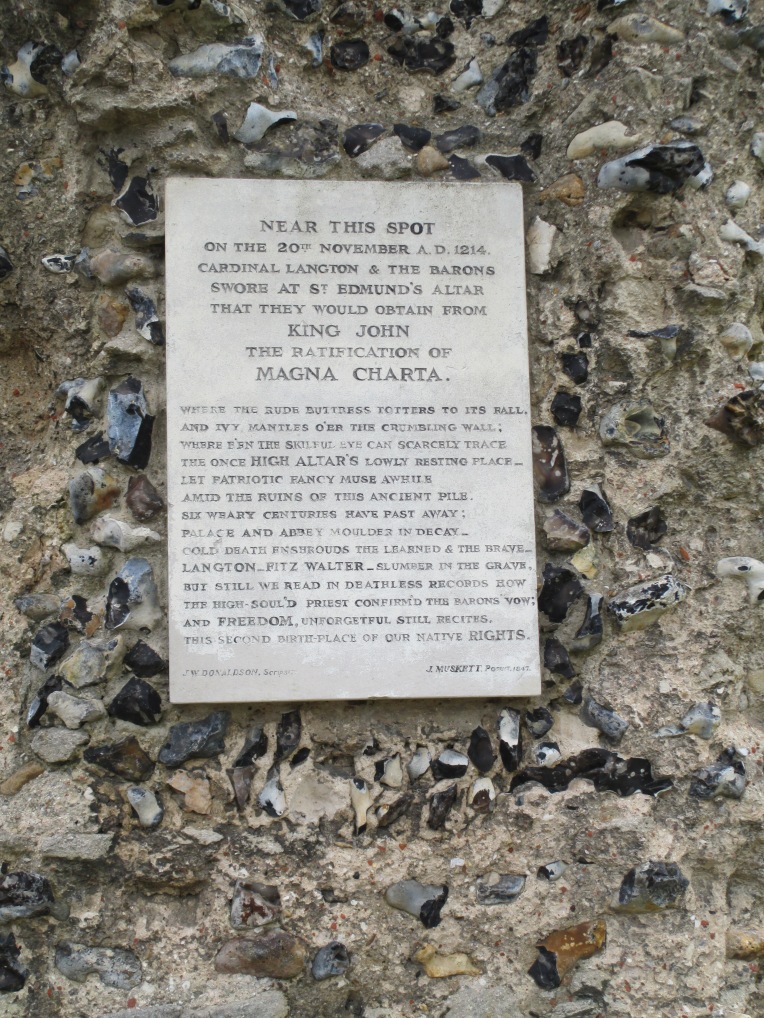

The role of the king and his lordship over the Barons was the core of the revolt. In 1214 in Bury St Emdunds 25 barons swore on the altar of St Edmund that they would try to force King John to accept the charter of liberties of Henry I, which was the precursor to the Magna Carta. The rough spot and the commemorative plaque can be seen in the photos below.

Ultimately, with help from the French the barons backed John into a corner. The Magna Carta was agreed to by King John on June 15th 1215 at Runnymede. Runnymede was neutral ground as it is located half way between London (which had gone over to the barons) and John’s castle at Windsor. Also being a water meadow it was a naturally occurring in-between liminal space.

The photos above are from the water meadows at Runnymede. Finding them was a bit of an ordeal. We got the train to the nearest station expecting there to be signs. This is a mistake I have made too many times before in relation to medieval sites. After getting sent in the wrong direction twice and accidentally dragging my mother through a swamp on her birthday we found the meadows (though we still missed the physical monument to the Magna Carta). I had very wet feet, but it was worth it. Apart from anything else it is a gorgeous example of an English water meadow. There are plaques in the town to some of the barons involved in the Magna Carta. You can see the one to William Marshal below.

The Charter wasn’t an end though and as an attempt to abate civil war it was less than useful. It took King John’s death in 1216 to mark the beginning of the end of the conflict. He died, probably of dysentery, at Newark after losing his entire baggage train in the Wash (A tidal inlet in Norfolk and somewhere else I got my feet very wet walking to). You can see a copy of John’s effigy below (the original is in Worcester Cathedral) and a photo of the Wash as it looked in 2012, significant land has been reclaimed for farming.

John’s death did not mean the immediate end of the civil war. His son Henry III took the throne, but he was only nine and the formidable William Marshal was appointed Regent of England.

A copy of Henry III’s effigy (the original is in Westminster Abbey

William Marshal’s effigy in the Temple Church in London (arguably)

William Marshal the Younger’s effigy (arguably) in the Temple Church in London.

William Marshal the Younger’s effigy (arguably) in the Temple Church in London.

Marshal is a man I’ve written about a lot before (I wrote my honours thesis on him) and you can find out more about him here. Marshal was an elder statesman by the time he became Regent in 1216. He was probably in his very late 60s. He had stayed loyal to King John at personal cost, and his son William Marshal the Younger had fought on the Barons’ side. It has been argued that this family divide was intentional to make sure there was a Marshal foot in either camp. Regardless, with John dead, barons started coming back into the royal fold, including eventually John’s half brother William Earl of Salisbury, who had jumped ship in the dying days of John’s reign. Ultimately more than 115 defected back, but it took some longer than others.

The effigy of William Earl of Salisbury in Salisbury Cathedral.

The effigy of William Earl of Salisbury in Salisbury Cathedral.

By the time John died Prince Louis was very much in England and not willing to give up his claim to the crown. Ultimately it took the Battle of Lincoln, which was so successful for the royalist forces that it was known at the Fair of Lincoln, winning the Battle of Sandwich (despite Louis’ ships being led by the pirate Eustace the Monk) and Marshal ultimately bribing the Prince to get him to go back to France. By the time Marshal died in May 1219 he left behind a, comparatively, stable England.

But where did all this turmoil leave the Magna Carta? Today there are four surviving copies of the original 1215 Magna Carta. One belongs to Lincoln Cathedral because Hugh of Wells the Bishop of Lincoln was present when the Magna Carta was sealed and made sure a copy was brought back to the cathedral

This copy is currently held in Lincoln Castle along with the 1217 Charter of the Forest which (in the name of Henry III, but under Marshal’s seal) was separated from the Magna Carta into its own individual document.

Lincoln Castle.

Lincoln Castle.

Another copy is held at Salisbury Cathedral. It was probably brought by Elias Dereham, a priest of the Archbishop of Canterbury and has remained there ever since.

Salisbury Cathedral.

Salisbury Cathedral.

The final two copies are housed in the British Museum. One most likely originally came from Canterbury, the other is known as the ‘London Magna Carta’ and exactly how it ended up in London by the 17th century is unknown. Sadly the Canterbury copy is illegible. It did suffer some fire damage in 1731, but most of the damage was done in a failed attempt to restore the Charter in the 1830s. Sadly this copy is the only surviving 1215 copy that still has the original seal of King John attached, though it was severely melted in the 1731 fire.

British Library.

British Library.

After the reign of Henry III the next key re-issue of the Magna Carta was by Edward I. In 1297 he issued (a revised version) officially into the English statutes. Interestingly enough I have actually seen one of the only surviving 1297 copies in Australia. It is held at Parliament House in Canberra. It is one of only four surviving copies and the only one in the Southern Hemisphere. It was bought by Australia’s Chief Librarian for 12 500 pounds in 1951.

Parliament House Canberra Australia.

Regardless of how little immediate effect the Magna Carta had, it is a document that has come to symbolise the core of Western Democracy. It has become mythology in its own right and its reality has got quite lost in the monumental legacy. A legacy that (right or wrong) Rudyard Kipling summed up best.

At Runnymede, at Runnymede,

What say the reeds at Runnymede?

The lissom reeds that give and take,

That bend so far, but never break,

They keep the sleepy Thames awake

With tales of John at Runnymede.

At Runnymede, at Runnymede,

Oh, hear the reeds at Runnymede:

‘You musn’t sell, delay, deny,

A freeman’s right or liberty.

It wakes the stubborn Englishry,

We saw ’em roused at Runnymede!

When through our ranks the Barons came,

With little thought of praise or blame,

But resolute to play the game,

They lumbered up to Runnymede;

And there they launched in solid line

The first attack on Right Divine,

The curt uncompromising “Sign!’

They settled John at Runnymede.

At Runnymede, at Runnymede,

Your rights were won at Runnymede!

No freeman shall be fined or bound,

Or dispossessed of freehold ground,

Except by lawful judgment found

And passed upon him by his peers.

Forget not, after all these years,

The Charter signed at Runnymede.’

And still when mob or Monarch lays

Too rude a hand on English ways,

The whisper wakes, the shudder plays,

Across the reeds at Runnymede.

And Thames, that knows the moods of kings,

And crowds and priests and suchlike things,

Rolls deep and dreadful as he brings

Their warning down from Runnymede!

References:

Site visits in 2012, 2015 and 2017.

Magna Carta: Law, liberty, legacy by the British Library ISBN: 9780712357630

Blood Cries Afar: The forgotten invasion of England 1216 by Sean McGlynn ISBN: 9780752488318

https://www.bl.uk/magna-carta/articles/magna-carta-an-introduction

https://www.bl.uk/magna-carta/articles/magna-carta-english-translation

https://www.visitlincoln.com/magnacarta

https://magnacarta800th.com/events/st-edmundsbury/

https://www.salisburycathedral.org.uk/magna-carta

https://www.aph.gov.au/Visit_Parliament/Art/Top_5_Treasures/Magna_Carta

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-02-05/australia-magna-carta/6072830

http://www.britannia.com/history/docs/kipling.html

The photos are all mine.

Excellent post. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, glad you enjoyed it

LikeLike

What an excellent account! Really well written. Magna Carta is a small step along the way, but at least it’s heading in the right direction. A few photos of the modern memorial – not built by us Brits, by the way, – are here http://bitaboutbritain.com/runnymede-and-magna-carta/

LikeLike

Thanks, your account is excellent too (and I’m glad we agree :)) The legacy of the Magna Carta has been so important, even if it’s immediate role was less dramatic. I really like your pictures of the modern memorials too. I knew they were there, but they are seriously hard to find on foot from the train station, and I found the meadows so I was very happy to just see them.

LikeLike

A fascinating article, a wonderful insight into that period of history. I love the wet feet on Penny’s birthday moment. All in the name of true reaserch. Wonderful. 😄

LikeLike

Thanks Lyn, glad you enjoyed it. I also succeeded in dragging her to a church that was closed (it said it was open on the website) and nearly getting us locked into a law complex. 🙂

LikeLike

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2018/07/friday-fossicking-27th-july-2018.html

Thank you, Chris

LikeLike

Thanks I appreciate it.

LikeLiked by 1 person